Reverse Land Banking

Protecting Prime Agricultural Land by creating 15-year mobile home pop-up communities that can be removed in a day, when prime ag land is needed for food.

Reverse Land Banking of Prime Farm Land

New Zealand is in the process of writing a National Policy Statement for Highly Productive Land (NPS). In its summary document it writes “Generally, the conversion of highly productive land to urban land-uses results in the irreversible loss of that land for primary production. While the conversion may not be strictly irreversible, higher land prices and smaller economic units mean that a return to primary production is generally very unlikely.” This is true for what is classified as buildings but not true for a temporal form of shelter, known as mobile homes. Concurrently, Ministry for the Environment is writing National Planning Standards in which it proposes a radical redefinition of the meaning of building to include mobile homes not fixed to land. In both cases, it appears mobile homes are becoming collateral damage due to ignorance on the part of policy writers.

Manufactured mobile homes are not fixed to land. They are made in factories in a month, towed to site and parked on land in a day, with no requirement for licensed professional services and no foundations, although some use storm anchors held by ratchet cables that can be removed in an hour. They are here today, gone tomorrow. Mobile homes serve an important role in housing affordability. Typical cost is $60,000 to buy, $250/week to lease. They are not buildings, therefore under the Land Transfer Act, they are not real estate, not part of the land, not annexed to title. Instead of highly productive land being subdivided into smaller economic units (allotments), they are chattel assigned a parking space through a right-to-occupy contract.

This is not a new concept. In Aotearoa, it predated colonialism, and Te Tiriti o Waitangi merged these indigenous legal concepts into common law. Te Tiriti offers three protections:

- Whenua: Land understood as life-providing, not real property as a commodity or investment

- Kainga: Village, community, the social and economic basis of cooperation and wellbeing

- Taonga Katoa: Valued property including tangible and cultural.

Whenua: Land is not regarded as an investment that can be bought or sold. It cannot be subdivided, or held by a sole owner. Land is permanent whereas its people and their land use is temporal – it comes and goes. Land not actively used by the tangata whenua could be provided as tuku to manuhiri, temporal people gifted a right to occupy so long as they need and use the land. This concept is relevant to NPS beyond tangata Māori.

Kainga: People lived in villages. Today, maraes tends to be a wharenui and wharekai. But in precolonial kainga, families lived in wharepuni, small homes about the size and function of today’s manufactured mobile home. The small sized worked because the public space outside the wharepuni was shared space. This wharepuni concept crosses over to the 21st century in the form of manufactured mobile homes. This is relevant to NPS.

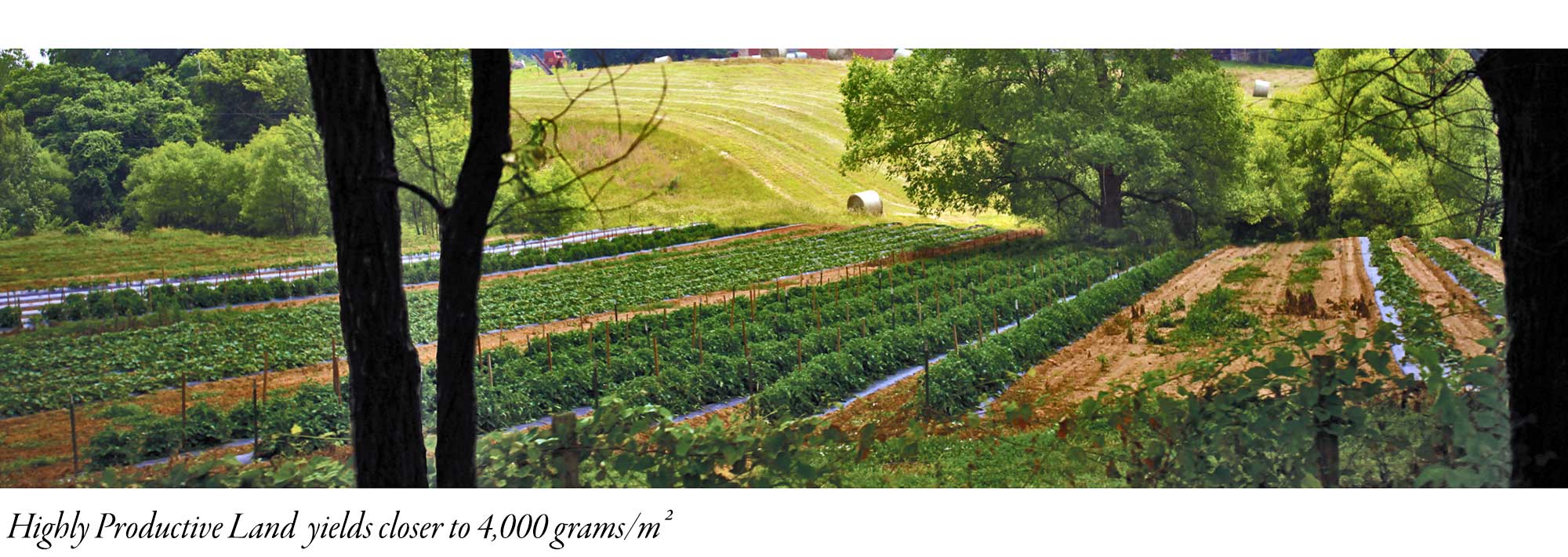

At present, very little NZ fertile land is highly productive because there is no pressing global need. NZ exports about 90% of the food it grows. Annually, dairy produces 80 grams of milk solids per m². Beef cattle is 65 g/m². Contrast this with market gardens that yield 4,000 g/m² of diverse foods. As the planet experiences middle-class population growth projected at 2 billion by 2030, New Zealand’s role in feeding the planet will demand it increase its productivity. At that point, 80 g/m² will be discredited; not deemed highly productive.

The Māori Wharepuni Kainga model has not been considered in the NPS because consultation on NPS was not on the industry’s radar screen. It only came into focus recently when council planners started referring to NPS as a basis for blocking resource consents for mobile home pop-up villages being proposed in response to the affordable housing crisis. Unlike subdivision of land for new housing (such as KiwiBuild), mobile home villages are temporal – typically 15 year plans to provide immediate warm, dry, affordable housing until central and local government can catch up with proper growth plans and outcomes for affordable housing.

This model is not just for Māori. It is a way of life that will fit many people, regardless of their cultural identity. But in terms of the NPS, it can be thought of as reverse land banking – a way to preserve NZ’s most fertile farm land in a way that meets today’s shelter needs while ensuring tomorrow’s food needs are protected.

Recommended Rules to Qualify

A Pan-iwi Wharepuni Kainga (mobile home pop-up village) is a temporary land use that enables the protection of prime, fertile farmland until it is needed to grow food. Real estate conversion of highly-productive land to urban land use with tends to be irreversible due to the increased value of subdivided sections, the future demolition requirements of improvements and the fact that during construction topsoil is usually stripped from the land and too often remaining topsoil is contaminated by construction debris (such as CCA sawdust) and later contaminated by resident activities. In contrast, the wharepuni kainga land use model does not subdivide, is not in the land but on the land, is easily removable and contains rules to protect the topsoil.

Legal Definition: A wharepuni kainga is a collection of multiple wharepuni in a village layout in which the land is not subdivided. Instead each wharepuni (unit or mobile home) and other temporal improvement is granted a time-limited right-to-occupy contract with the same expiration date for all units.

Chattel with a right-to-occupy: Under law, each unit is chattel, not real estate, not annexed to title, not fixed to ground, not a building, not a structure. The land use is temporal, not permanent.

Normal freehold title or Māori title: It is not how the land is owned, but how land use is granted. Fee simple or Māori title, and its zoning status as protected productive farmland remains unchanged, but with a temporary fixed-term residential land-use permit to hold the land in a form of reverse land bank until needed for food growing.

Kainga Structure: Living in a wharepuni or mobile home requires a balance of public and private space. Public space may be several large marquees designed to be removed when the kainga land use ends.

Dining marquee (wharekai) may have a BBQ and picnic tables where people can eat in common. It could include portable food carts where entrepreneurs prepare and sell food and drink.

Workshop marquee (whare whaihanga) may have tools where people can make and sell tangible property to earn a living or to fashion taonga (furniture, provisions, etc.) for local use. Also the kainga may include gardens and food production.

Meeting marquee (wharenui) may have benches and tables, used for childcare, classes and community meetings. Also may include sports fields.

These public spaces, plus outdoor space for gatherings, provide for shared activities that build strong, supportive communities. This means private space (mobile homes) can be smaller. Like the wharepuni, the commons facilities must be removable in a matter of days, leaving no trace other than bare soil.

No foundations: All units must be mobile, meaning not fixed to land, not attached to foundations. Units may be connected to ground anchors using ratchet cables or equivalent to prevent movement in storms.

Unit Site: Each unit is assigned a site upon which the unit is installed. This includes a surrounding “defensible space” that is private to the resident and may be delineated with easily-removable fencing.

Standpipes: The primary land change is the installation of underground pipes and conduit and standpipes for each fixed site. This is compatible with future fertile land use and will remain when the kainga is removed. The potable water pipes provide irrigation. The wastewater pipes can provide liquid nutrient supply and the conduit can power robotic farming equipment that may become prevalent in the future.

Carpark: No cars in the kainga. All cars are parked on a carpark at the entrance that is constructed by laying down an impermeable cover (blocks contaminant dripping) over good topsoil that is covered with crushed rock or paverstones. This ensures when the kainga is removed, the carpark is removed as well.

Paver Footpaths: Paverstones or other removable media connect the carpark to each unit, suitable for walking, cycling, wheelchairs, walkers, and in the case of larger kainga, wide enough for e-quads: small four-wheel electric vehicles the size of golf carts.

No contaminants: No petrol-powered devices (lawn mowing must use electric power or sheep), no chemicals, no CCA sawdust or other contaminants that may have toxic long-term effects on the topsoil.

Fees: Under the National Planning Standards for wharepuni kainga, land-use permits should be granted as a Matter of National Importance, meaning that for the most part, it is granted by Kainga Ora. Because the residents of such kainga will tend to be NZ’s most vulnerable, central and local government fees, charges and other cost-recovery taxes (by whatever name) should be limited to no more than $500 in initial fees. It is recommended a fixed cost recovery fee of $120 per year automatically collected monthly, (0.002 similar to the Auckland general rate) be applied to each unit and paid to the host territorial authority in lieu of rates.