Seeking a High Court Declaration

Overview

Problem

Since 2018, several ministries have made it their mission to interfere with the mobile home industry by asserting building rules (structures fixed to land and to perform for no less than 50 years) apply to mobile homes.

They argue this is for health and safety although no evidence exists that the homes manufactured by NZ mobile home manufactures are unsafe or unhealthy.

The problem with applying building standards to mobile homes is building rules are not fit for purpose. Buildings are designed to remain in one place, mobile homes are designed to be relocated as often as annually. Limiting design to approved materials/methods inhibits innovation and suppresses the industry.

However, the big problem is the consenting process which can easily add $5,000 to $25,000 to the cost of a $75,000 unit, and introduce time delays where instead of 2-weeks in a factory, it can be 2 months or more to coordinate inspections.

Further, while a host family/whanau is OK with tuku whenua (a license to occupy for a while… informal permission to park a mobile home on the land and live next door), the permanent erection of a building on their land is too complicated and too entangling.

The industry is typical of NZ. The largest may make 20 units/month, but most are lower volume. None have the resources to fight MBIE, MFE, NZTA and the councils.

Since 2017, a number of them have quit. They find fighting the government is too hard, too aggravating and too expensive.

Government lost in a bubble

The affordable housing crisis gets worse every day. When Labour took power in Oct 2017, the state house waiting list had about 6,000 families, many of whom have access to family or whanau land, but can’t afford to build on it.

Today, that waiting list has over 24,000 families; growing at about 400 per month every month. And that is only the families who qualify to be listed on the waiting list. Far more are living in cars, tents, garages and overcrowded conditions but on no registry.

Mobile Homes are an immediate, interim solution that can be manufactured in two weeks, installed in two hours and provide a warm, dry, safe, comfortable and affordable solution until the government can implement permanent solutions to end the crisis.

One would expect government would embrace this private-sector solution that costs the taxpayer nothing, can be implemented immediately and is completely reversible when the need for it passes.

However, instead of supporting innovation, councils prosecute. MBIE makes determinations inconsistent with case law and earlier determinations. MFE wrote into the National Planning Standards interpretations that are contrary to Common Law, and NZTA says towing a 3m wide mobile home is illegal because it does not qualify for a WOF, but the same unit can be towed on a trailer.

This is regulatory creep. It is not sanctioned by law. It deprives the nation of a real solution to the affordable housing crisis.

Resolution

Common Law began in 1066 when William the Conqueror claimed absolute ownership of all land in England, and over all fixtures attached or annexed to land. This type of property is called realty or real estate and in 2022, it remains the core basis of land law and of Sovereignty. By virtue of the Treaty of Waitangi, the Crown holds absolute ownership over all realty in New Zealand, issuing a bundle of rights today called the Record of Title as found on the LINZ Land Register.

Excluded from realty is chattel, or personal property, meaning property not fixed or annexed to land. A castle is realty and is subject to the rights of ownership granted by the Crown. But a traveler’s caravan parked on the village green belongs absolutely to the person, not the Crown or the village.

Mobile homes are – by definition (because they are mobile) – chattel, not realty.

The need for a High Court declaration is solely due to regulatory creep – that the personnel in the ministries and the councils seem to have formed a closed-bubble in which they view mobile homes as some sort of loophole exploiters who must be defeated. An examination of the record will show how they have evolved their interpretations of law, without either noticing or caring that in doing so they are turning the fundamental basis of land law upside down.

It’s not only bad policy, it’s bad law.

To date, court cases are as matters of fact pitting the resources of the council against a small business or low-income individual. A few then go to MBIE where MBIE finds for their peers in council. When it gets to court, in clean cases, such as Dall v MBIE, the council and MBIE are soundly defeated, but District Court rulings are non-binding. Further many of these cases are messy questions of fact that enable lawyers to obfuscate questions of law.

A High Court Declaration has no such complications. There are no matters of fact. It is solely a declaration as to what the law means. Factual examples can be presented, but in the end the court will declare the legal meaning of building, structure and fixed/ annexed to land.

This of course is not the end of the matter.

The Crown holds power to do what it wishes. Through Parliament the Crown can change the law, and if it chooses to it may conflate chattel with realty.

But to do so has far reaching implications that undermine the fundamental basis of NZ’s unwritten constitution. Among others, mortgage banks, insurance companies and conveyancing lawyers would be likely to oppose in the strongest terms, as it would take decades and millions to sort case law.

MHA hopes the declaration will break through the government bubble, to get the respective ministries to see the value of chattel housing and the need for fit-for-purpose rules.

Such regulations need a two-prong approach. MHA member are manufacturers. They mass produce units. They need type approvals with features and options. The other group are DIY tiny-home makers, typically made for themselves, their family or friends. They need guidance to ensure health, safety & buyer protection should they later sell their creation.

The Elements of a Declaration

- All Buildings are Structures

- All Structures are Realty

- All Realty is Land or Fixed/Annexed to Land

The first two legal principles should attract no debate. They are fundamental to Common Law, Land Law and Sovereignty.

The Third is a continuum that has been subject to centuries of case law and jurisprudence. MHA will ask the court to make a delineation creating three “zones”: black, grey and white.

Black: no argument, it is realty.

White: no argument, it is chattel.

Grey sets out the areas where each case becomes a matter of fact to be determined in a court of law.

MHA seeks to have clarity so its members can tailor the design of their products to ensure their products remain in the white zone, so they then can negotiate with government on regulations that give the industry certainty.

Particulars

Fixed to land means annexed to title. As Sir John W. Salmond observed in his landmark book, Jurisprudence, this becomes a matter of intent. Coins buried in the ground do not become realty, they are no different than coins in ones pocket. But a pile of stones (chattel) become realty when made into a wall.

MHA seeks a declaration that mobile homes remain chattel until they are intended to be annexed to title, or clearly are fixed to land.

The most obvious fixing is to build a foundation – be it concrete and steel in the ground, or piles driven into the earth with mechanical fixings to the structure above.

White Zone:

Owner declares intent is chattel and the unit is not fixed to land, not attached to a foundation or to piles (but it is OK for the unit to sit on blocks for stability or be tied to wind pegs).

Connected to water, power and wastewater using caravan-type connectors, not requiring a licensed professional to attach/detach

Capable of being transported over land without being significantly taken apart or destroyed. OK to bolt units together, and add protective flashing, etc, provided such can be removed within a day and easily replaced on redeployment.

If on axles and wheels, OK to unbolt and store them when not in use.

Can be moved by tow, truck or on a trailer

NZTA rules irrelevant to Building Act/RMA interpretation (as per earlier MBIE determinations).

Clarify s8 Building Act: if it is not a structure under s8(1)(a), 8(1)(b)(iii) is irrelevant

Black Zone:

Owner declares intent is realty. Fixed to land/ Annexed to title. Fixed to a foundation. Requires a licensed professional to connect or disconnect water, wastewater, power, etc. Requires significant structural disassembly to move on public roads due to size.

Law

On Movable and Immovable Property

On Movable and Immovable Property

Sir John W. Salmond is considered an inaugural or founding father of not only a law school, but also of a New Zealand jurisprudence. He was the former Solicitor General of New Zealand and in 1902, he wrote Jurisprudence. The 12th edition 1966 is still cited and his comments on moveable and immovable property offers clarity of thought as relevant in 2021 as in 1902.

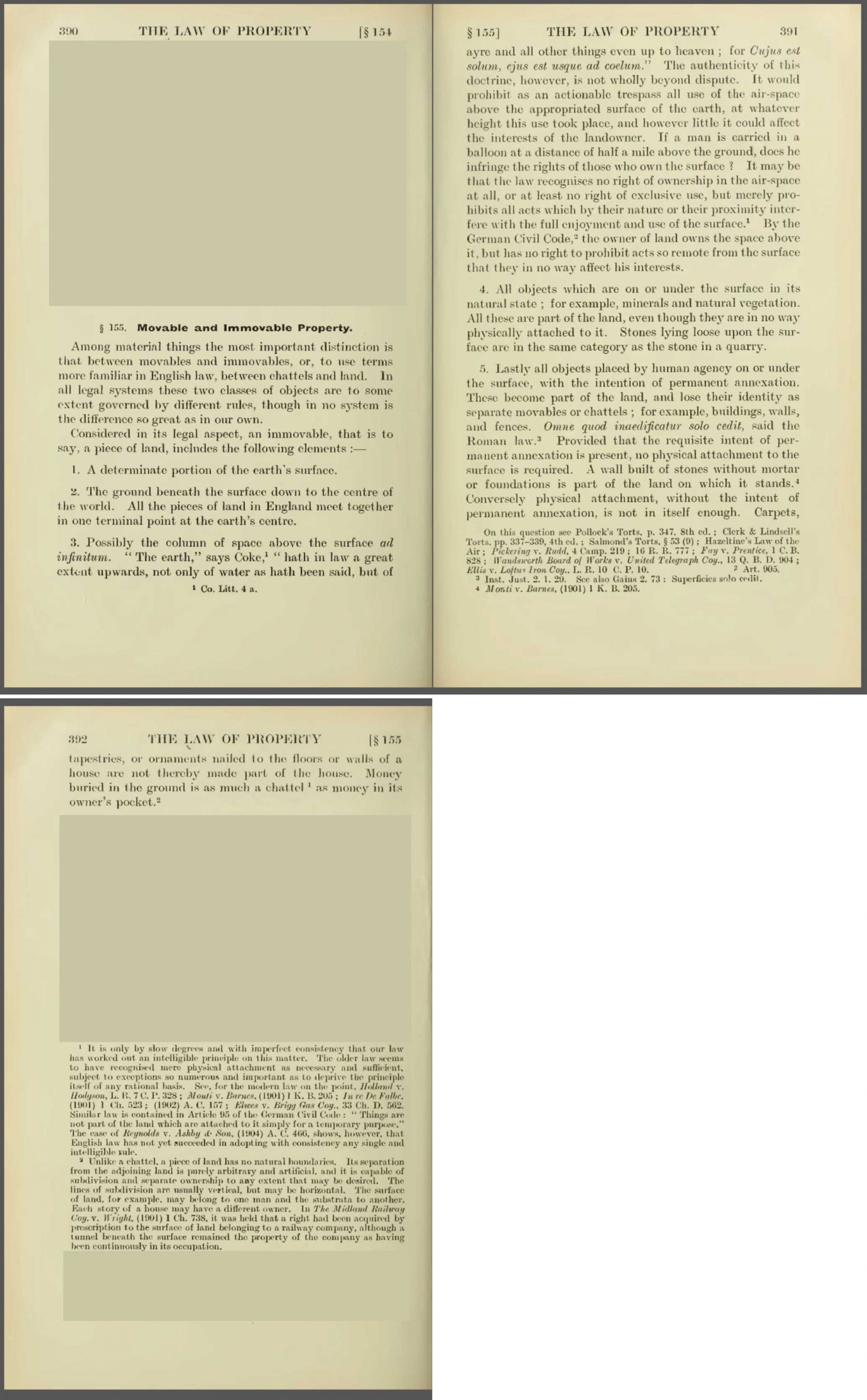

A PDF of the 4th edition can be found here . Start at page 392 (pdf page 408). See print screen below.

In §155. Movable and Immovable Property, Salmond sets out the elements for immovable property (i.e. land):

Among material things the most important distinction is that between movables and immovables, or to use terms more familiar in English law, between chattels and land. In all legal systems these two classes of objects are to some extent governed by different rules, though in no system is the difference so great as in our own.

5… all objects placed by human agency on or under the surface with the intention of permanent annexation. These become part of the land, and lose their identity as separate movables or chattels; for example buildings, walls and fences. Omne quod inaedificatur solo cedit [Everything which is erected on the soil goes with it] said the Roman Law. Provided that the requisite intent of permanent annexation is present, no physical attachment to the surface is required. A wall built of stones without mortar or foundation is part of the land on which it stands. Conversely, physical attachment, without the intent of permanent annexation, is not in itself enough. Carpets, tapestries, or ornaments nailed to the floors or walls of a house are not thereby made part of the house. Money buried in the ground is as much a chattel as money in its owner’s pocket.

Footnote 2: Unlike a chattel, a piece of land has no natural boundaries. Its separation from the adjoining land is purely arbitrary and artificial, and it is capable of subdivision and separate ownership to any extent that may be desired.

The word annexation is laden with legal meaning. It is about intent. If a land owner wishes to make a mobile home becomes a building, they apply for consent to build a foundation, show the home meets the health, safety and durability requirements for a building, and the chattel ceases to be personal property and becomes realty. It not only is fixed to land, but annexed to title. It loses its independent identity.

In practical terms this happens by fixing it to a foundation, but also by registering it on the Property Title (Records of Title). The two acts – paper and physical – are one act and they cannot be bifurcated. Annexation, where the paper act (digitally recorded since the Land Transfer Act 2017) is inextricably tied to the physical act of fixing to land. As Salmond says, physical attachment, without the intent of permanent annexation, is not in itself enough.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi

The marriage of Māori tikanga with Common Law is relevant to the question of the legal status of movable property.

Te Tiriti promises the Crown will protect tino rangatiratanga over whenua, kainga and taonga katoa.

Whenua is land, but whenua is not realty. While under the English Treaty, Māori ceded sovereignty of all lands to the Crown, under tikanga, this is impossible because the land owns the people, not the other way around. The people are the guardians of the land; they are born and die, whilst the land remains. Curiously, this view of land gradually is being adopted by western culture and the idea of conquest and confiscation is losing support. Tikanga and Common Law are merging into a new, more enlightened understanding of human life on Earth.

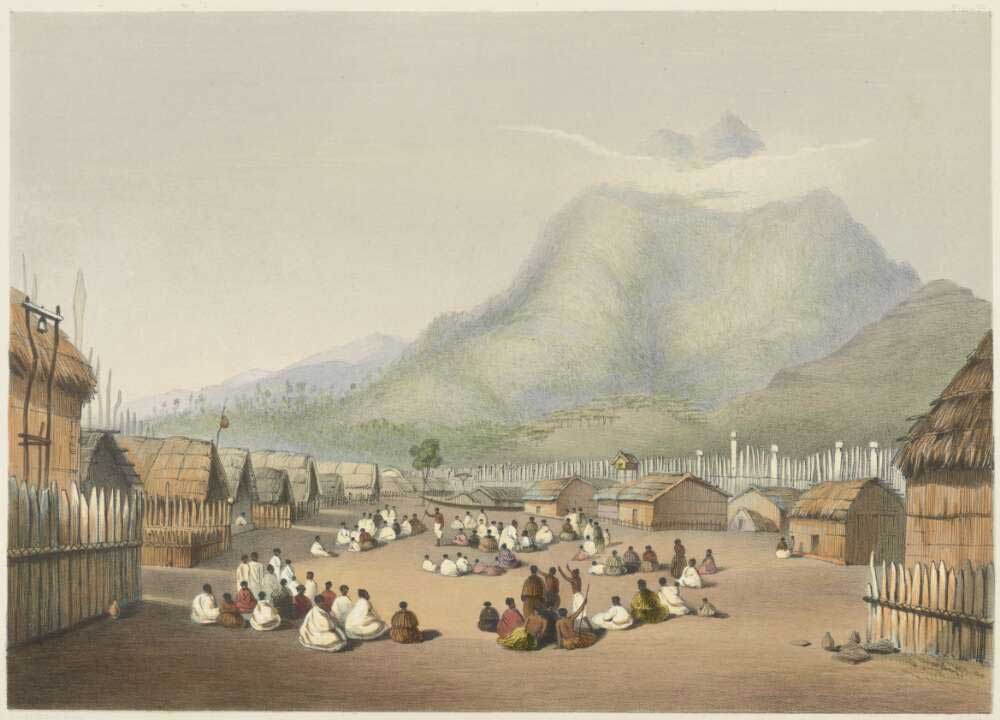

Kainga is the village. It is on the whenua, and is how people live as a community.

Taonga katoa is all that the people value, and this includes the wharepuni – the small family homes shown in the painting of a kainga, above. Wharepuni are more akin to the modern day mobile home than the English building. They exist to provide shelter for as long as it is needed, but their connection to the land is transitory.

Māori are disproportionately represented in the hidden homeless, especially in rural lands. They need housing now, but the red tape required – especially when the land is in Māori title – means they remain sleeping in cars, tents, garages and overcrowded conditions.

While this declaration seeks clarity in Common Law, it is relevant to tikanga. Indeed, most mobile homes have the same relationship to land as whenua – most notably tuku whenua, which is a right or permission to occupy, in contrast to mana whenua which is based on being tangata whenua. Just as Te Tiriti promises tino rangatiratanga to nga tangata katoa o Nu Tirani, this modern form of tuku whenua (permission to occupy) is the basis of most mobile home placement regardless of whether the owner is Pakeha or Māori.

Typically a family member owns the land, and has an elderly parent, or grown children with family of their own, unable to buy or rent adequate housing. The family member who owns the land gives permission to bring a mobile home onto the land. Typically, they plug the mains power from the mobile home into the main house, attach a potable water hose to an outdoor tap and connect wastewater the same as is done with a caravan. Some remove the wheels and put the mobile home on blocks so it does not bounce and in extra high wind zones they may affix pegs or bolts to keep from moving in storms.

There is no need for the council to become involved, except if the additional bedrooms exceeds the waste water system, or if the unit is too close to a side yard or exceeds the allowable density.

Equally important is intent regarding annexation. A right to occupy does not annex the chattel to the realty. The host who owns the land does not gain ownership by the guest parking it on the land. If the bank forecloses on the land, they have no right to be mobile home. It is the same as cars parked there.

Legal research

Legal research

Skerritts v Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions (No.2)

Cardiff Rating Authority v Guest Keen Baldwin’s Iron and Steel Co (1949)

Cheshire CC v Woodward [1962] 2 Q.B. 126; [1962]

Case Law

Skerrits v Secretary of State for the Environment [2000]

SKERRITTS OF NOTTINGHAM LIMITED Appellant – v – THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT, TRANSPORT AND THE REGIONS [2000] EWCA Civ 5569 Case No. QBCOF 1999/0690/C. Relevant sections include:

- The words which were used in the context of rating in that case upon which the judge and Mr Katkowski, who appears for the respondent, rely, are to be found in the judgments of Denning LJ and Jenkins J. Denning LJ said this:

“A structure is something of substantial size which is built up from component parts and intended to remain permanently on a permanent foundation; but it is still a structure even though some of its parts may be movable, as, for instance, about a pivot. Thus, a windmill or a turntable is a structure. A thing which is not permanently in one place is not a structure but it may be, ‘in the nature of a structure’ if it has a permanent site and has all the qualities of a structure, save that it is on occasion moved on or from its site. Thus a floating pontoon, which is permanently in position as a landing stage beside a pier is ‘in the nature of a structure’, even though it moves up and down with the tide and is occasionally removed for repairs or cleaning.”

- Jenkins J said this:

“It would be undesirable to attempt, and, indeed, I think impossible to achieve, any exhaustive definition of what is meant by the words, ‘is or is in the nature of a building or structure’. They do, however, indicate certain main characteristics. The general range of things in view consists of things built or constructed. I think, in addition to coming within this general range, the things in question must, in relation to the hereditament, answer the description of buildings or structures, or, at all events, be in the nature of buildings or structures. That suggests built or constructed things of substantial size: I think of such size that they either have been in fact, or would normally be, built or constructed on the hereditament as opposed to being brought on to the hereditament ready made. It further suggests some degree of permanence in relation to the hereditament, ie, things which once installed on the hereditament would normally remain in situ and only be removed by a process amounting to pulling down or taking to pieces.” (Underlining is in the court document)

Barvis v Secretary of State for the Environment [1971]

Mr Justice Bridge thought it was wrong to substitute issues of real property law and cases on fixtures for the statutory definition in the 1990 Act. Instead he found assistance from a case on the meaning of building or structure for the purposes of rating (Cardiff Rating Authority v Guest Keen Baldwin’s Iron and Steel Co (1949)). The judge in that case picked out 3 factors which, while not conclusive, would indicate that something was in the nature of a building or structure. These are:

- substantial size – such that it has or would normally be constructed on the land and not ready made;

- some degree of permanence – so it would normally remain in place and only be removed by pulling down or taking to pieces; and

- physical attachment, although the fact that something is not so attached is not conclusive.

The judge also observed that a limited degree of motion does not necessarily prevent something from being in the nature of a structure.

‘If, as a matter of impression, one looks objectively at this enormous crane, it seems to me impossible to say that it did not amount to a structure or erection.’

This 93 page pdf of Appendices is a good place to start in referencing relevant case law: http://publicaccess.wokingham.gov.uk/NorthgatePublicDocs/00338942.pdf

Start on Page 33

The approach of the courts in construing the definitions has been to ask first whether what has been done has resulted in the erection of a “building”: if so, the court “should want a great deal of persuading that the erection of it had not amounted to a building or other operation” (Barvis Ltd v Secretary of State for the Environment (1971) 22 P. & C.R. 710 at 715, per Bridge J.). Following that approach, in R. (on the application of Westminster City Council) v Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions [2002] J.P.L. 58; Jackson J. set aside the Secretary of State’s decision that the stationing of a wooden kiosk (2.14m square, and 2.7m high) at Covent Garden did not require planning permission. He held that the Secretary of State had erred in focusing on the question whether the placing of the kiosk was a building operation, instead of the question whether the kiosk in its final form was a building.

In the Barvis case, the Divisional Court placed reliance upon a passage in the judgment of Jenkins J. in Cardiff Rating Authority v Guest Keen Baldwin’s Iron and Steel Co Ltd [1949] 1 K.B. 385 (subsequently endorsed by the Court of Appeal in Skerritts of Nottingham Ltd v Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions (No.2) [2000] 2 P.L.R. 102) which identified three primary factors as being relevant to the question of what was a “building.”

- size: a building would normally be something which was constructed on site as opposed to being brought already made to the site. But it may nonetheless be on a small scale, such as a model village (Buckinghamshire County Council v Callingham [1952] 1 All E.R. 1166). Nonetheless, where the operations are quite insignificant, they may be regarded as de minimis, and outside control: see, e.g. the planning appeal decision at [1977] J.P.L. 122 (boundaries of “leisure plots” marked out by about a dozen metal pegs interlaced with two strands of nylon rope).

- permanence: a building, structure or erection normally denotes the making of a physical change of some permanence. In Skerritts of Nottingham Ltd v Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions (No.2) [2000] 2 P.L.R. 102 the Court of Appeal upheld an inspector’s decision that a marquee that was erected on a hotel lawn every year for a period of eight months was, due to its ample dimensions, its permanent rather than fleeting character and the secure nature of its anchorage, to be regarded as a building for planning purposes. The annual removal of the marquee did not deprive it of the quality of permanence. Permanence did not necessarily connote that the state of affairs was to continue forever or indefinitely. The importance of permanence is illustrated by the following decisions: in James v Brecon County Council (1963) 15 P. & C.R. 20 the Divisional Court declined to find any error in a ministerial decision that the erection of a battery of fairground swing boats, capable of being lifted and taken away complete by six men or dismantled in about one hour, did not constitute development. Similarly, the mere stationing of mobile caravans and touring caravans on land would not be taken to involve any building operation, having regard to the factors of permanence and attachment: Measor v Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions [1998] 4 P.L.R. 93. On the other hand, where a number of self-build chalets and sheds had been erected and suspended on pillars on land, it could be assumed that they were all erected with a prospect of permanence, and as a matter of objective judgment they would have to be regarded as “structure or erections” for the purposes of the Act: R. v Swansea City Council Ex p. Elitestone Ltd (1993) 66 P. & C.R. 422.

- physical attachment: this is in itself inconclusive, but weighed against the other factors may tilt the balance. Thus, in Cheshire County Council v Woodward [1962] 2 Q.B. 126 the Divisional Court declined to disturb a ministerial finding that no development had occurred when a wheeled coal hopper and conveyor between 16 and 20 feet high had been brought on to the appeal site; but in Barvis Ltd v Secretary of State for the Environment (1971) 22 P. & C.R. 710 the erection of a large scale tower crane running along rails was held to constitute development notwithstanding that it was capable of being dismantled and being erected elsewhere. In Tewkesbury Borough Council v Keeley [2004] EWHC 2594 (Q.B.) Jack J. held that certain sheds that were mobile, to the extent of having wheels so they could be moved about a site, did not constitute buildings, and that planning permission had not been required for their stationing on agricultural land. Nor did this constitute an “other operation” under s.55(1): if there was no building operation because the shed was not a building, then it fell outside the potentially apposite category and should be treated as outside the section.

The above factors were discussed and applied in R. (on the application of Hall Hunter Partnership) v First Secretary of State [2006] EWHC 3482 (Admin) (polytunnels for soft fruit production). The High Court upheld the inspector’s decision that agricultural polytunnels constructed by machinery on top of legs penetrating 1 metre into the ground constituted operational development due in part to their degree of attachment to the land. At [18] Sullivan J. considered the evidence that “it took teams of 10 men 45 man hours to fully erect 1 acre and 32 man hours to dismantle the same”, “machines were used to screw the legs up to 1m deep into the ground and to bend straight lengths of metal into arcs to create the hoops” and “3.9ha (or 9.6 acres) would on that basis have taken over 430 hours (or about a week’s work for the 10 man team, assuming no over time) to erect and over 300 hours for them to dismantle” and in such circumstances held at [19] –

“In view of the fact that machines were used to screw the “vast number of … legs needed” up to one metre into the ground, it is not surprising that the inspector concluded “the polytunnels have a substantial degree of physical attachment to the ground”. “‘Permanence’ does not in this context necessarily connote a state of affairs which is to continue forever or indefinitely. It is matter of degree between the temporary and the everlasting” (see per Morritt L.J. at 1036 of Skerrits). The fact that a large and well constructed structure is capable of being, and is, dismantled and removed annually for a short time is not determinative (see per Pill L.J. at 1035 of Skerrits). If one asks how long must a structure or erection remain in situ for there to have been a sufficient degree of permanence, the answer is: “for a sufficient length of time to be of significance in the planning context” (see per Schiemann L.J. at 1034 of Skerrits). The inspector’s finding that the polytunnels “would remain in one particular location from between three and seven months in any one year” (para.54) is not challenged. His conclusion that “even the shortest of those periods of time would be a sufficient length of time to be of consequence in the planning context and more so in respect of the longer periods” cannot be said to be unreasonable.”

In R. (on the application of Save Woolley Action Group Ltd) v Bath and East Somerset Council [2012] EWHC 2161 (Admin); [2013] Env. L.R. 8 Lang J. held that the local planning authority had adopted too narrow an approach to the meaning of development when considering the application of the 1990 Act to certain poultry units. The units in question were described as follows:

(i) the poultry units would house 1,000 laying hens, each weighing 2kg;

(ii) each unit was approximately 20 metres by 6 metres by 3.5 metres high;

(iii) the units were not fixed to the ground, but were on metal skids to allow them to slide along the ground when pulled by a tractor;

(iv) if extreme winds were forecast they could be held down with metal spikes;

(v) each unit would weigh about 2 tonnes (in addition to the 2 tonne flock of hens);

(vi) each unit would be in a fenced paddock of 1-2 acres and would stay in the paddock;

(vii) the units would be moved within their paddock regularly (approximately every 8 weeks) by being dragged by a tractor or 4×4;

(viii) each unit could be assembled by a ‘skilled’ team from metal hoops, metal skids, uPVC planks, polythene and insulation in ‘a couple of days’. If the metal hoops were not taken apart then the shed could be dismantled in 3-4 hours;

(ix) the units had slatted floors, manually operated conveyor belts, drinkers, feeders and integral lighting. They were powered by an onsite generator;

(x) the units were supplied with mains water by means of a hosepipe connection to standpipes located alongside the access track.

Lang J. held that the term ‘building’ in s.336(1) had a wide definition which included “any structure or erection” and this definition has been interpreted to include structures which would not ordinarily be described as ‘buildings’ ([69]). Given, in particular, the substantial weight and size of each unit the local planning authority should have considered whether the units fell within s.336(1). In concluding that the units were chattels and not buildings as they could be moved around the site, the authority had erred. Permanence had to be considered in terms of “significance in the planning context” and “the ability to move [the units] around the field did not remove the significance of their presence in planning terms” ([75]). The works carried out to construct the units were capable of falling within s.55(1)(A)(d) “other operations normally undertaken by a person carrying on business as a builder”.

Guidance in relation to the meaning of building operations may also be obtained from Ministerial decisions. For example, an inspector held that the erection in a pub garden of three large umbrellas in concrete footings and attached together with canvas side shades amounted to the erection of a building (Ref: APP/H5390/C/1128513); an inspector held that the erection of a large stainless steel sculpture constituted a building operation (Ref: APP/K5600/X/10/2140909 and [2011] J.P.L 822); but an inspector held that the installation of a freestanding cash dispensing machine on a garage forecourt was not a building operation (Ref: APP/22830/C/06/2009917).

Elitestone Ltd. v. Morris and Another[1997]

Degree of annexation

The importance of the degree of annexation will vary from object to object. In the case of a large object, such as a house, the question does not often arise. Annexation goes without saying. So there is little recent authority on the point, and I do not get much help from the early cases in which wooden structures have been held not to form part of the realty, such as the wooden mill in Rex v. Otley (1830) 1 B. & Ad. 161, the wooden barn in Wansborough v. Maton (1836) 4 Ad. & El. 884 and the granary in Wiltshear v. Cottrell (1853) 1 E. & B. 674. But there is a more recent decision of the High Court of Australia which is of greater assistance. In Reid v. Smith [1905] 3 C.L.R. 656, 659 Griffiths C.J. stated the question as follows:

-

- “The short point raised in this case is whether an ordinary dwelling-house, erected upon an ordinary town allotment in a large town, but not fastened to the soil, remains a chattel or becomes part of the freehold.”

The Supreme Court of Queensland had held that the house remained a chattel. But the High Court reversed this decision, treating the answer as being almost a matter of common sense. The house in that case was made of wood, and rested by its own weight on brick piers. The house was not attached to the brick piers in any way. It was separated by iron plates placed on top of the piers, in order to prevent an invasion of white ants. There was an extensive citation of English and American authorities. It was held that the absence of any attachment did not prevent the house forming part of the realty. Two quotations, at p. 667, from the American authorities may suffice. In Snedeker v. Warring, 2 Kernan 178 Parker J. said:

-

- “A thing may be as firmly fixed to the land by gravitation as by clamps or cement. Its character may depend upon the object of its erection.”

In Goff v. O’Conner, 16 Ill. 422, the court said:

-

- “Houses in common intendment of the law are not fixtures, but part of the land. . . . This does not depend, in the case of houses, so much upon the particular mode of attaching, or fixing and connecting them with the land, upon which they stand or rest, as upon the uses and purposes for which they are erected and designed.”

Purpose of annexation

Many different tests have been suggested, such as whether the object which has been fixed to the property has been so fixed for the better enjoyment of the object as a chattel, or whether it has been fixed with a view to effecting a permanent improvement of the freehold. This and similar tests are useful when one is considering an object such as a tapestry, which may or may not be fixed to a house so as to become part of the freehold: see Leigh v. Taylor [1902] A.C. 157. These tests are less useful when one is considering the house itself. In the case of the house the answer is as much a matter of common sense as precise analysis. A house which is constructed in such a way so as to be removable, whether as a unit, or in sections, may well remain a chattel, even though it is connected temporarily to mains services such as water and electricity. But a house which is constructed in such a way that it cannot be removed at all, save by destruction, cannot have been intended to remain as a chattel. It must have been intended to form part of the realty. I know of no better analogy than the example given by Blackburn J. in Holland v. Hodgson, L.R.7 C.P.P. 328, 335:

-

- “Thus blocks of stone placed one on the top of another without any mortar or cement for the purpose of forming a dry stone wall would become part of the land, though the same stones, if deposited in a builder’s yard and for convenience sake stacked on the top of each other in the form of a wall, would remain chattels.”

Commentary: As noted in the bold text, A house which is constructed in such a way so as to be removable, whether as a unit, or in sections, may well remain a chattel, even though it is connected temporarily to mains services such as water and electricity. Mobile homes are called mobile for a reason. They are manufactured (not constructed) to be removable. Their purpose is to provide housing when it is needed, and to be removed, complete and intact when no longer needed, to be parked on the next allotment anywhere else including at the other end of the country where shelter is required for a period of time.