This section is under construction

Over time, the references in law become a moving target. This section is under construction, with some duplication in content. Apologies, as it requires time to update.

This section may be of general interest, but it primarily serves lawyers and those involved in potential litigation or public officials seeking clarity on confusing law.

Relevant Law Links

Last updated 2021

Building Act Section 8 (meaning of building)

Resource Management Act §2(1) (meaning of structure)

Land Transport Act §2(1) (meaning of vehicle)

Section 6.6 of Land Transport Rule 41001 (overwidth)

§2(1) Land Transfer Act 2017 (meaning of land inc building)

LDAC constitutional principles and values of NZ law

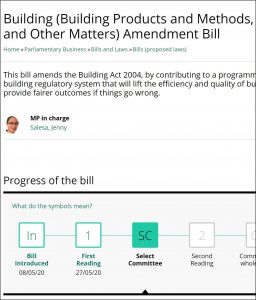

Building (Building Products & Methods…) Amendment Bill

Jurisprudence-John-William-Salmon (see p 390)

Ministries Undermining Law

Part 1 of the Fundamental constitutional principles and the rule of law says Legislation should be consistent with fundamental constitutional principles. Officials should carefully consider the impact of fundamental constitutional principles on proposed legislation

The word building is a fundamental constitutional principle of Common Law harking back to 1066.

- The Land Transfer Act 2017 (5)(1) says land includes— (a) estates and interests in land: (b) buildings and other permanent structures on land: (c) land covered with water: (d) plants, trees, and timber on or under land. This is the foundation of property law, which is the earliest law of Common Law. Land includes buildings. Buildings are fixtures attached to land and annexed to title. This is the constitutional basis on tenure.

- The Building Act 2004 says building— (a) means a temporary or permanent movable or immovable structure (including a structure intended for occupation by people, animals, machinery, or chattels); and(b) includes— (iii) a vehicle or motor vehicle (including a vehicle or motor vehicle as defined in section 2(1) of the Land Transport Act 1998) that is immovable and is occupied by people on a permanent or long-term basis; A building is a structure. A structure is fixed to land. Both building and structure are fixed to land and annexed to title.

- The Resource Management Act 1991 says structure means any building, equipment, device, or other facility made by people and which is fixed to land; and includes any raft. In each of these laws, the constitutional meaning of building is preserved.

But in 2019 the National Planning Standards created a new meaning: building means a temporary or permanent movable or immovable physical construction that is: (a) partially or fully roofed; and(b) fixed or located on or in land; but excludes any motorised vehicle or other mode of transport that could be moved under its own power.

This wordsmithing would be easy to miss in a 72 page document that ostensibly is to bring consistency to district plans. Indeed it only attracted 50 submissions, almost all from insiders, because the industry and the tens of thousands of existing mobile home occupants knew nothing about it. It was de facto usurpation of policy-making by anonymous civil servants focused on dealing with converted shipping containers and what MFE calls small mobile/relocatable buildings.“

It is accepted that as factories manufacture prefabricated forms of shelter, they will become more popular and may not fit the district plans that presume all shelter are buildings. But the way to address that is not to undermine fundamental constitutional principles.

The word “building” is one of the most time-tested words in law, along with land, fixture and structure. The new forms of shelter that have internal integrity so they can be delivered to land as a whole, and removed from land as a whole, with no significant effect on the land are different than buildings and structures. They need their own classifications, and had MFE done this there would be no controversy, except to ensure grandfathering of existing portable shelter.

The solution for this can be simple. The cabinet should adopt three resolutions and one instruction:

- Building in the National Planning Standards has the same meaning as in the Building Act 2004 §8

- Structure as referenced in the Building Act 2004 §8 has the same meaning as in the RMA §2(1)

- Mobile homes that are not fixed to land are neither structures nor buildings.

- Instruct MBIE, MFE, NZTA to advise all district councils (both planning and building consent authorities) to abide by the current law as confirmed by the above resolutions.

Then initiate a process in cooperation with the industry and representatives of the people who will live or use such facilities to come up with fit-for-purpose regulation appropriate for habitat that is mobile (can be here today, gone tomorrow)

Meaning of Words in Law

Last updated 2021

Quicquid plantatur solo, solo credit

(whatever is attached to the soil becomes part of it).

A Mobile Home is not a building unless it is fixed to land

A Mobile Home is not a structure unless fixed to land

The Building Act (8)(1) says:

Building : what it means and includes.

building—

(a) means a temporary or permanent movable or immovable structure (including a structure intended for occupation by people, animals, machinery, or chattels); and

(b) includes— … (iii) a vehicle or motor vehicle (including a vehicle or motor vehicle as defined in section 2(1) of the Land Transport Act 1998) that is immovable and is occupied by people on a permanent or long-term basis; [the Land Transport Act defines motor vehicle as “a vehicle drawn or propelled by mechanical power; and (b) includes a trailer;” [emphasis added]

The RMA, 2(2) Definitions says:

structure means any building, equipment, device, or other facility made by people and which is fixed to land… [emphasis added]

The Building Act seems to confuse many building control authorities because they read past the 9th word “structure”, without paying attention to it. Structure has a very specific meaning in law that is at the very core of Common Law and Sovereignty. Unfortunately, the question has become obfuscated and is laden with recycled ignorance.

Taking away all the qualifiers, building means a… structure. Or put another way, all buildings are structures, and if something alleged to be a building is not a structure, it is not a building, and therefore is not covered by the Building Act. It is not an exemption (like a 10 m² building), it is excluded from the Act. The BCA has no authority and asserting it is ultra vires (beyond their authority).

What is the meaning of the word “structure”?

The word structure has constitutional legal meaning, backed by both statute and case law. Before analysing the meaning of the word structure, review the basics of New Zealand constitutional law: In law, there is a generally accepted hierarchy of meaning:

- Subsection of the Statute in question

- Definition section of the Statute in question

- Definition section of Statutes having the same subject matter

- Interpretation Act

- Common Law including stare decisis

- Butterworths New Zealand Law Dictionary by Peter Spiller

- Oxford Dictionary of Law (British)

- Black’s Law Dictionary (American)

- New Zealand English Dictionary

- Other comprehensive (not vernacular) English dictionaries

- Google search

In the Building Act, the word “structure” is not given meaning, therefore one goes to the 3rd test, where the RMA says structure means any building, equipment, device, or other facility made by people and which is fixed to land…

If one seeks further clarity, under Common Law one goes to Commonwealth Case Law, where one finds that Skerritts v Secretary of State speaks clearly to the question:

SKERRITTS OF NOTTINGHAM LIMITED Appellant – v – THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT, TRANSPORT AND THE REGIONS [2000] EWCA Civ 5569 Case No. QBCOF 1999/0690/C. Relevant sections include:

- The words which were used in the context of rating in that case upon which the judge and Mr Katkowski, who appears for the respondent, rely, are to be found in the judgments of Denning LJ and Jenkins J. Denning LJ said this:

“A structure is something of substantial size which is built up from component parts and intended to remain permanently on a permanent foundation; but it is still a structure even though some of its parts may be movable, as, for instance, about a pivot. Thus, a windmill or a turntable is a structure. A thing which is not permanently in one place is not a structure but it may be, ‘in the nature of a structure’ if it has a permanent site and has all the qualities of a structure, save that it is on occasion moved on or from its site. Thus a floating pontoon, which is permanently in position as a landing stage beside a pier is ‘in the nature of a structure’, even though it moves up and down with the tide and is occasionally removed for repairs or cleaning.”

- Jenkins J said this:

“It would be undesirable to attempt, and, indeed, I think impossible to achieve, any exhaustive definition of what is meant by the words, ‘is or is in the nature of a building or structure’. They do, however, indicate certain main characteristics. The general range of things in view consists of things built or constructed. I think, in addition to coming within this general range, the things in question must, in relation to the hereditament, answer the description of buildings or structures, or, at all events, be in the nature of buildings or structures. That suggests built or constructed things of substantial size: I think of such size that they either have been in fact, or would normally be, built or constructed on the hereditament as opposed to being brought on to the hereditament ready made. It further suggests some degree of permanence in relation to the hereditament, ie, things which once installed on the hereditament would normally remain in situ and only be removed by a process amounting to pulling down or taking to pieces.” (Underlining is in the court document)

This makes it clear that for something to be a structure, it must be:

- Of substantial size that it either is or normally would be built on the allotment rather than being brought on the allotment ready made

- Once installed it would normally remain in situ

- Intended to remain permanently on a permanent foundation

- Removed by pulling it down or taking it to pieces

The test therefore is much simpler:

Is the unit in question fixed to land?

If not:

- It is not a structure and therefore

- It cannot be a building; and therefore

- The Building Act does not apply and therefore

- Building Control Authorities who demand application for a Building Consent, or who issue a Notice to Fix are exceeding their authority.

- The authorities are acting ultra vires.

Beyond this clear definition, the Act further limits the authority in regard to motor vehicles. It refers to the Land Transport Act meaning of motor vehicle, which says “includes a trailer”. Due to a lack of understanding of law, this is misread. Anything not fixed to land is not a structure, but not all structures fixed to land are buildings. A mobile home or a mobile trailer home that is fixed to land may be a structure, but not a building.

A structure fixed to land that is “intended for occupation by people, animals, machinery, or chattels) is considered a building. But a mobile home (either self-powered or trailer) is only considered a building if it is fixed to land and is occupied by people on a long-term or permanent basis. This means a mobile home that is fixed to land (usually bolted to a foundation), but is intended for occupation by animals, machinery or chattels (or left empty, used as a water tank or whatever) is not a building under the Act. An example would be a caravan that has had its axles removed and its frame bolted to a foundation that is used as a hen house, or a tool room or to store clothing. This caravan is a structure, but is not considered a regulated building under the Building Act even though it is fixed to land.

Consider some of the common errors committed by councils

- A council that says a mobile home or caravan is a building because it is occupied by people more than say 2 months a year is wrong. It must also be fixed to land.

- A council that says a mobile home is a building because its wheels have been removed is wrong, unless the trailer is also fixed to land.

- A council that says a mobile home is a building because it is over 10 m² is wrong.

- A council that says a mobile home is a building because it is not registered with LTSA, or cannot legally be towed on public roads because of its width is wrong.

However, being wrong does not mean councils cannot bully. They can and do abuse their powers. They can issue abatement orders. They can take matters to MBIE Manager Determinations who also has shown a failure to understand the legal meaning of structure. They can harass and make people’s lives miserable. And in fact they do so. None of this is legal, but it is real and it is wrong.

Then we get to a deeper question: Rules versus reason.

The MBIE Manager Determinations argues that regulation is necessary to ensure health and safety of the occupants. But the councils do not act because someone is concerned about health and safety. They act because the target has been dobbed in by their neighbour – who is not concerned about the target’s health and safety. In almost all cases, the neighbour does not like the target or feels that the target is cheating the rules.

New Zealand used to be a pragmatic country where authorities used reason and common sense. People living in mobile homes were left alone unless there really was a danger to their health or safety. This is changing, but this is due to personalities, not law. The law has not changed. It’s only recycled ignorance being passed among personnel that has caused de facto erroneous interpretation. Reason has given way to rules, and rules given way to mass dereliction through ignorance.

As shown by the leaking house crisis, in the case of large structures made by multiple parties, errors in construction can have catastrophic effects, a Building Code is important to ensure health and safety of the occupants who live in typical buildings.

But mobile homes are different from the scale of buildings properly addressed under the Building Act. Because of the limits inherent in mobility, mobile homes are small, simple, easy to repair, low cost and inherently safe and healthy.

- The skill set to build them is different than that required of licensed building practitioners. The skill set is that of coach maker.

- They must be sufficiently durable to arrive without damage after being towed on the worst of NZ’s substandard roads – worse than the rare shocks of earthquakes.

- In the case of fire, all exits are a single door or window away, a few metres at most, and all at ground level.

- They require little to heat or cool.

- All components can be accessed for repair in a matter of hours, not months.

The legal complications if they are considered buildings.

Buildings lose their independent identity and become part of the land, annexed to title. This means a WINZ rental unit owned by an investor, with rent paid direct by WINZ, and parked on a 3rd party’s land (perhaps a church or charitable trust) becomes the property of the land owner. Technically, the investor has lost their investment. The land owner gets the unit for free, and if the land has a bank mortgage, the bank must give permission (which it will not) for the unit to be moved off site. The paperwork alone to prevent this will be more than the revenue earned by the lease. It appears no one has thought this through.

Conclusion

Mobile homes and mobile trailer homes, by whatever name (tiny home on wheels, caravan, mobile cabin, etc) are chattel, not buildings unless they are fixed to land. Case law suggests fixing means attaching to a foundation. Unless those conditions are met, the BCA is acting ultra vires in interfering.

Further, one must ask why the BCA voluntarily would seek to take on legal liability that it assumes when it issues consent for a building. It makes no sense.

For decades, the mobile home industry operated quietly and without crisis. Now, as the nation faces an affordable housing crisis, in the name of the Crown, central and local government officials are creating an artificial crisis that will remove an affordable housing solution through death-by-regulation. Improper regulation that serves no good purpose.

Is regulation needed? Perhaps. But not building regulation. Mobile homes are not like buildings. They need fit-for-purpose regulation that does not increase costs by 50%, as happens when such units are fixed to land.

Meaning of Fixed to Land

Last Updated Oct 2022

All buildings are structures

All structures are realty

All realty is land or fixed to land.

Property Law: Property law is the oldest common law. It has changed little since 1086 with the Domesday Book. In common law, property is divided into two types: realty (real property or real estate) and chattel (personal property).

Real property (realty) includes land and everything fixed to land including fixtures, structures and buildings. All buildings are structures, all structures are realty, all realty is either land or fixed to land. Fixed to land means the fixture loses its independent identity and becomes part of the land and annexed to the title to the land.

Personal property (chattel) is property not fixed to land; property that retains its own independent identity. It does not attract rates and is not subject to foreclosure on land.

Chattels and Land:

The distinction between chattel and land (realty) is firmly established in Common Law. It was best set out by Sir John W. Salmond, former Solicitor General of and Supreme Court Judge in NZ, who in 1902 wrote Jurisprudence.

In §155. Movable and Immovable Property, Salmond explains the elements of immovable property (i.e. land):

Among material things the most important distinction is that between movables and immovables, or to use terms more familiar in English law, between chattels and land. In all legal systems these two classes of objects are to some extent governed by different rules, though in no system is the difference so great as in our own …

5…all objects placed by human agency on or under the surface with the intention of permanent annexation. These become part of the land, and lose their identity as separate movables or chattels; for example buildings, walls and fences. Omne quod inaedificatur solo cedit [Everything which is erected on the soil goes with it] said the Roman Law. Provided that the requisite intent of permanent annexation is present, no physical attachment to the surface is required. A wall built of stones without mortar or foundation is part of the land on which it stands. Conversely, physical attachment, without the intent of permanent annexation, is not in itself enough. Carpets, tapestries, or ornaments nailed to the floors or walls of a house are not thereby made part of the house. Money buried in the ground is as much a chattel as money in its owner’s pocket.

Footnote 2: Unlike a chattel, a piece of land has no natural boundaries. Its separation from the adjoining land is purely arbitrary and artificial, and it is capable of subdivision and separate ownership to any extent that may be desired.

Salmond’s footnote 2 is most helpful. Land has no natural boundaries. Land as property is an arbitrary and artificial construct of society. A mobile home has a natural boundary.

Means and Includes

Having established the difference between realty and chattel, there is one more distinction to be clarified: the words means and includes when used in drafting law:

The NZ Law Commission Legislation Manual Structure and Style section on DEFINITIONS speaks to how Building Act section 8 (p51) is structured:

208 In drafting definitions, use means if the complete meaning is stipulated. Includes is appropriate if the stipulated meaning is incomplete. Do not use the phrase means and includes. It is impossible to stipulate a complete and an incomplete meaning at the same time. In an unusual case it may be appropriate to use the formula means . . . and includes . . . if the function of the second part of the definition is to clarify or remove doubt about the intended scope of the first part of the definition:

This distinction is essential to understanding Section 8 of the Building Act 2004 because part 8(1)(a) begins with the word means whereas part 8(1)(b) begins with the word includes. In other words, (a) is a stipulation whereas (b) is a clarification and in the specific case of Section 8 (b) is a limitation meaning it is an exclusion to the stipulation.

This most important distinction appears to have not been raised by appellants in the several court cases, not considered by the judges in rendering decisions and ignored by MBIE in drafting determinations.

Analysis of Section 8 of the Building Act 2004

|

8. Building: what it means and includes (1) In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires, building— (a) means a temporary or permanent movable or immovable structure (including a structure intended for occupation by people, animals, machinery, or chattels); and (b) includes—…(iii) a vehicle or motor vehicle (including a vehicle or motor vehicle as defined in section 2(1) of the Land Transport Act 1998) that is immovable and is occupied by people on a permanent or long-term basis |

The Act governs buildings. Its Section 8 sets out the scope of the Act’s authority:

Section 8(1)(a) begins with the word “means”, thus (1)(a) stipulates the complete meaning.

Section 8(1)(b) begins with the word “includes”, thus (1)(b) offers further clarification.

Subpart (1)(b) limits the authority of (1)(a) by exclusion – in other words, while something technically may be embraced by (1)(a), the Parliament in its wisdom decided it was not necessary to be subject to the NZ Building Code (NZBC).

Subpart (1)(b)(iii) is an exclusion. If all buildings are structures, and all structures are fixed to land, then a vehicle (such as a trailer) only becomes a building when it is both rendered immovable and occupied by people on a permanent or long-term basis. What is missing from this subpart? Occupation by animals, machinery or chattel as well as short-term occupation by people.

Example: In rural NZ there are old buses and caravans embedded in soil (rendered immovable) used as a chook house or tool room, or during hunting season as a short-term sleepover hunting cabin. While the vehicle lost its independent identity and became a part of the realty, the Parliament in its wisdom saw no need to require it comply with NZBC. But if a poor family moves in long-term, NZBC applies.

Section 8 Legal Analysis

Structure – the subject of Section 8

Sequentially, in determining the reach in the Building Act, one must first examine that which has been stipulated by the use of the word “means”. This is found in section 8(1)(a) which consists of a noun (structure) and modifying adjectives (temporary or permanent movable or immovable). This creates a hierarchy of questions:

Is the object a structure or is it not? If not, stop here, the Act does not apply.

If yes, is it temporary or permanent, movable or immovable? This covers all bases.

If it is a structure, is it a vehicle? If not a vehicle, stop here, the Act applies.

Is the vehicle both immovable and occupied by people on a long term or permanent basis? If not or if only one of the two variables, stop here, the Act does not apply.

As can be seen, therefore, the first test differentiates between chattel and realty. The Act clearly only concerns itself with realty. However, this is where MBIE and several district councils do not appear to understand the basis of Common Law, thus in extending their regulatory reach, they make ultra vires interpretations.

Referencing Sir John Salmond above, the first test becomes simple. Is the intent of parking the mobile home on the property permanent annexation?

In the United States, mobile homes became manufactured homes under 1975 federal legislation that acknowledged mobile homes were different than buildings. In addition to setting consistent national standards as to their manufacture, the end buyer of such a unit could choose either to designate it as chattel or realty. The latter has a benefit in losing its independent identity in that it can be financed and insured as a building, and it can increase the land value higher than the cost of the unit. However, it also becomes subject to property tax (rates). Other buyers choose for it to remain as chattel because the costs are lower. This clearly acknowledges Salmond’s point that the determinate is the intention of the buyer because the unit itself is convertible. It is designed so it can either be chattel or realty.

New Zealand lacks a Manufactured Home Act, however Salmond’s test still applies, where one can examine the facts to discern the owners intention:

If the mobile home has its axles removed and its chassis permanently secured to a foundation, including piles, slab or a concrete foundation, then clearly it is intended to be realty. It has been made a structure, and is subject to the NZBC as a building.

However, if it is not fixed to a foundation, and it is engineered so it can easily be uplifted and removed without significant damage or destruction, then it is intended too remain as chattel, retaining its independent identity with a natural boundary disconnected to the land. It is not a structure, not a building; not subject to the NZBC.

Mobile home manufacturers design their products as rentals where they intend to remove the unit when the lease expires. They generally require a license to occupy from the land owner. All mobile homes are designed in this way, even if the unit is sold. In other words, the default design of factory-made mobile homes is as chattel.

Temporary” & Moveable – Modifying Elements

Modifying Elements in a stipulation: Adjectives modify the subject (noun), but they do not alter the fundamental meaning of it. Thus, the word structure in Section (1)(a) does not change its time-tested common law meaning. To do that properly, because it is such a fundamental change to the most ancient of principles – as so clearly expressed by Salmond above (Among material things the most important distinction is that between movables and immovables, or to use terms more familiar in English law, between chattels and land). This would not be done by a casual insertion of adjectives, but would have a clear definition signposting a change in common law – and in this case would be unlikely to get to first reading because the Parliamentary Council Office would most likely object and advise expressing Parliamentary intent (determining the reach of the Act) in a way that did not radically change the underpinnings of property and common law.

Therefore, it is reasonable to accept the adjectives in Section (1)(a) (temporary or permanent, movable or immovable) do not change the stipulated meaning of structure to embrace chattel as well as its common law meaning as realty. If so, why are temporary and movable there, and what do they mean in determining the reach of the Act?

Temporary: It is common in NZ for a new landowner to build a temporary bach in which to live while they earn the money and gradually build their permanent home. The Parliament, in its wisdom, includes this type of structure in the reach of the NZBC because the health and safety of the occupants does not change because they intend to pull it down in three years when their permanent home is finished and receives consent to occupy.

However, if that same landowner were to buy or lease a mobile home, a caravan or a converted bus instead of building a bach, while it meets the test of temporary, it does not meet the test of the subject: structure. Therefore, it is outside the reach of the Act.

Movable: There are many degrees of movable. Movable is not the same as mobile. This is not a new question, and there are long-established precedents that have examined it.

In Skerritts v Sec of State [2000] EWCA Civ 5569 Case No. QBCOF 1999/0690/C it states

““A structure is something of substantial size which is built up from component parts and intended to remain permanently on a permanent foundation; but it is still a structure even though some of its parts may be movable, as, for instance, about a pivot. Thus, a windmill or a turntable is a structure. A thing which is not permanently in one place is not a structure but it may be, ‘in the nature of a structure’ if it has a permanent site and has all the qualities of a structure, save that it is on occasion moved on or from its site. Thus a floating pontoon, which is permanently in position as a landing stage beside a pier is ‘in the nature of a structure’, even though it moves up and down with the tide and is occasionally removed for repairs or cleaning.”

Skerrits goes on to write:

“It would be undesirable to attempt, and, indeed, I think impossible to achieve, any exhaustive definition of what is meant by the words, ‘is or is in the nature of a building or structure’. They do, however, indicate certain main characteristics. The general range of things in view consists of things built or constructed. I think, in addition to coming within this general range, the things in question must, in relation to the hereditament, answer the description of buildings or structures, or, at all events, be in the nature of buildings or structures. That suggests built or constructed things of substantial size: I think of such size that they either have been in fact, or would normally be, built or constructed on the hereditament as opposed to being brought on to the hereditament ready made. It further suggests some degree of permanence in relation to the hereditament, ie, things which once installed on the hereditament would normally remain in situ and only be removed by a process amounting to pulling down or taking to pieces.”[Underlining is in the original]

In summary, the judges make clear a structure is first and foremost determined by intention, where movable can be a characteristic without changing its nature as a structure. They give the example of a windmill and a floating pontoon. Further they make clear it is intended to normally remain in situ, where removal amounts to pulling it down or taking to pieces.

Another example of the difference between moveable and mobile might be a bed. A bed in a prison is immovable, permanently fixed to the jail cell. A bed in a hospital if bolted to the floor may be part of the realty, even though its mattress is movable with motors to enable patients to sit up in bed. An ambulance gurney is mobile and would never be considered realty.

Consider the example of house removal companies. A building becomes chattel when it is uplifted by a house removal company. The act restores independent identity to the unit while it is towed down the road and even when stored on pallets in the removal yard, awaiting a buyer. The removal company would not be required to secure a building consent to park it in its yard for sale. The house only loses that independent identity when it is fixed to a new foundation on the buyer’s land.

Salmond gives the example of a stone wall as part of the realty, even if only held by gravity, and can be moved stone by stone. When the land is sold, the buyer expects the stones to remain.

In conclusion, movable is not the same as “mobile”. A mobile home is not a movable structure, it is mobile shelter/chattel.

If a mobile home is parked on bank financed land, but not fixed to the land, and the bank forecloses on the land, it does not take ownership of the mobile home parked on it, and its owner may tow it away.

Indeed, this is made clear on bank refusal to finance homes on Māori title land. Banks will not loan on any Māori building fixed to land because they cannot foreclose on Māori title. They do not finance movable structures, because such a structure is part of the Māori title. But they will finance mobile homes at the higher interest rate and shorter terms for vehicles.

Likewise, conveyancers make clear to buyers and sellers of real estate that chattels, including mobile homes, must be a separate contract, or a separate schedule to be included in the purchase agreement. A building on the land is part of the land, but chattels must be separately listed and agreed by both seller and buyer.

Consider these statements made by conveyancers:

Chattels vs Fixture – Movable property is a chattel, this is property that can be removed without causing damage to the property. (Inder Lynch, Lawyers)

A chattel is any moveable item that is not permanently attached to the land or building (not a fixture). The Conveyancing Shop

Fixtures are permanently attached to the property (for example, a deck, showers and electrical wiring) and are included with the land title. All other moveable items are chattels and are only included in the sale if they are listed in the sale and purchase agreement. Chattels are personal property that is not fixed to the property and can be removed without causing damage. www.settled govt.nz

Similarly, council rates are based on realty. Mobile property is not considered a rateable improvement, and mobile property is not listed on the property valuation

Consider these council explanations:

Quotable Value (Council’s valuation service provider) determines the value by looking at the selling price of similar properties in the area. Valuations do not include chattels. Wellington City Council

Capital value is the mostly likely selling price of the whole property at valuation date. It includes buildings and improvements. It does NOT include chattels, stock, crops, machinery or trees. Kaipara District Council

As mobile homes become more common, councils may argue they should not get the benefit of council services without paying for them. Building owners pay through rates, but as chattel, mobile homes are outside the reach of rating valuation.

This is a legitimate concern, but the answer is not to distort the meaning of building to include chattel. There is a much simpler way, but it requires legislation.

Establish a national registry of mobile homes, and charge an annual license fee that is then shared with the territorial authority where the mobile home is located on the day of assessment. Typical general rate value on a $100,000 realty improvement (a building) might be $200 per year. Rather than add the expense of variable valuation, set a fixed fee of say $200 of which the national registry takes say $20 to record, collect and disperse and $180 to the host council. Since many mobile homes are on lease, and are annually moved by the lessor from one council jurisdiction to another, this ensures the fee goes to the council providing the general services.

Until such legislation is adopted, it should be noted that the majority of persons who would be assessed such a fee are in the lowest income brackets, and if there are 10,000 mobile homes currently in NZ, the total collection might be $2 million per annum for the whole country. The 2019/20 accommodation supplement in NZ cost $1.7 billion.

The UK has a capital gains tax, thus it must have a clear distinction between chattel and realty. Consider this explanation:

The word ‘chattel’ is a legal term meaning an item of tangible, movable property – something you can both touch and move. Your personal possessions will normally be chattels. Including:

- items of household furniture

- paintings, antiques, items of crockery and china, plate and silverware

- motor cars, lorries, motorcycles

- items of plant and machinery not permanently fixed to a building

Private cars are exempt from Capital Gains Tax and many chattels having only a limited lifespan are also exempt. (See the guidance on wasting assets*). But if you dispose of any other chattel, you may be liable to Capital Gains Tax.

A wasting asset is an asset with a predictable life of 50 years or less. When you dispose of an asset, you estimate its predictable life based on the nature of the asset and your intended use of the asset when you originally acquired it. Certain chattels are always treated as wasting assets, for example, plant or machinery.

The UK example is another reason why the PCO would be unlikely to accept a definition of building that conflates realty with chattel. NZ does not have a capital gains tax, but is considering it. Mobile homes and converted shipping containers are wasting assets that have a predictable life of 50 years or less, whereas buildings are required to have a performance standard of 50 years or longer.

Subframe: A practical test between movable vs mobile can be the subframe. A mobile unit must have a strong enough subframe that it can move under its own weight without damage to anything fixed to it. Thus a container or a mobile home on wheels or on skids must have a strong subframe with lifting points that support the full weight and integrity of the unit. In contrast most buildings would fall if moved in the same way.

Vehicle – Exclusionary modifiers

Vehicle: When is s8(1)(b)(iii) the vehicle test applied?

As explained in The NZ Law Commission Legislation Manual Structure and Style section on DEFINITIONS (see above), when legislation includes the word “includes”, it is to clarify, or in the case of Section 8, to exclude specific circumstances where the subject in question fits the test (that is can be considered to be a structure), but is not deemed sufficiently important to be included in the powers of the Act.

This is the case with Section 8(1)(b)(iii), the vehicle test.

As an exclusion, while a former vehicle that becomes immovable, or is intentionally made to be immovable (such as fixing to a foundation) and is occupied on a long term basis by animals (say chickens), machinery or chattel, or only occupied by people on a short term basis (say as a bed for hunters during hunting season, farm workers during picking season or children visiting their grandparents farm during school holiday), the Parliament in its wisdom deemed such structures as not of sufficient risk to require coverage under the Building Code. Their concern is to ensure the health and safety of people who, for whatever reason, but generally due to poverty, find they must live long-term in a former vehicle as their home. In such cases, the law sets a high bar in terms of compliance with the Building Code. The former vehicle must be safe, warm and durable. A person who moves an old school bus on a site and fixes it to a foundation is likely to be issued a notice to fix, not be able to comply and thus must move out.

In determining when s8(1)(b)(iii) applies, the object in question must first have passed the stipulated test of 8(1)(a), and found to have be a structure. It next must be tested to ensure there is not an exclusion.

The first (1)(b)(iii) test asks if it is occupied by people on a long-term or permanent basis. This immediately places objects occupied by animals, machinery or chattel outside the reach of the Act. In the case of mobile homes that have already been found to be structures, however, this is not the case, as they are designed for long-term permanent occupation by people.

The second (1)(b)(iii) test then asks if the mobile home is immovable. This question has already been discussed above, but for clarity is revisited herein.

Immovable is more restrictive than movable or immovable. Immovable means it is not able to be moved. Movement is as simple as a windmill or pontoon. In practical terms, one may presume a vehicle is designed to be mobile on wheels, and it would be rendered immovable if embedded in concrete or intentionally bolted to a foundation. It is a question of fact if a vehicle is immovable because it has been left so long the chassis is stuck in the mud, but that legal grey area is far outside the concern of mobile homes that are intentionally designed to be mobile and presumed to remain so.

Thus, as a matter of law, the only place where the (1)(b)(iii) test applies is a former vehicle that became a structure by being rendered immovable and occupied by people on a long-term or permanent basis. Thus, if the vehicle is occupied by animals, tools or chattel, or by people on a short-term or temporary basis, even if it is immovable, it is excluded from NZBC and from Building Control Authority.

Unfortunately, recent MBIE determinations and litigation to date overlooks the distinction between means and includes as discussed above, thus both MBIE and judges have erroneously conflated the two parts of s8.

In the hierarchy of means and includes, if a mobile home is found not to be a structure, because it is not part of the realty, the further question of vehicle is superfluous. However, because the word vehicle is in Section 8, like a moth to flame, many lawyers and judges have jumped to it, without considering the hierarchy of means and

Even so, because mobile homes are vehicles, in clear cases like Dall v MBIE, the judge tosses out the assertions by MBIE Determinations based on testing the vehicle exclusion. Right outcome based on wrong interpretation of Section 8.

Conclusion

It is acknowledged the law is inadequate regarding mobile homes. To date, there have been no catastrophic failures like the $20 billion leaky building crisis, but this is because manufactured mobile homes have single source liability.

A factory that manufactures a mobile home is fully liable for its performance. Unlike a building where liability is spread over many parties, a factory-made product is not. In-so-far as investors in a factory do not wish to lose their investment due to product liability losses, they have inherent incentive to ensure their product is safe, healthy, durable and fit for purpose.

Further, limited by the width, height and weight constraints of public roads, mobile homes are necessarily simple. Fire safety is less of a concern when the living space has no more than a few meters to an outside door or window, and all escape routes are at ground level. The simple rectangular shape with a maximum height limit of 4.2m from road to top means a design that is highly energy efficient. Durability begins with the necessity to hold together on long road trips with destinations on rural, often unpaved roads, thus in earthquakes, mobile homes bounce, but do not break apart. Unlike buildings where structural refurbishment can be exceedingly, sometimes prohibitively expensive due to access, all components of a mobile home, including the chassis are easily accessed. Indeed, if a steel under-chassis corrodes, it can be repaired after lifting on simple car jacks or a garage hoist.

As noted above, while the current rating system does not extend to people living in chattel, but enjoying the same benefits of people living in rateable buildings, the actual rates take would be minimal given the median valuation of a mobile home.

Never-the-less, it may be time to consider legislation that specifically addresses alternatives to structures. The building industry is one of the most outdated industries in the 21st Gradually, it is moving toward premanufactured components that are assembled on site, not constructed. A mobile home is a fully manufactured living space where there is no on-site assembly at all, solely a 2-hour installation. The preparation, such as connecting a standpipe with utilities, still requires a building consent, and may be denied, if for example, the host wastewater system is a septic tank already at maximum capacity.

The government should turn its focus to working with the mobile home industry to develop a national standard for mobile homes and a national registry so they can easily be tracked as they move from one council district to another (many new mobile homes include GPS trackers).

Such regulation should include minimum standards, but these should not add cost to the mobile home. For example, instead of complex, prescriptive calculations for insulation, a simple test limited heat loss to X hours when a unit is heated to 20° in a 10° chilled space and the heat is then turned off. Type certificate should be approved, but the cost should be paid by the taxpayer as a matter of national interest, not the start-up manufacturer for whom such testing either becomes a barrier for market entry, or is passed on to the mobile home buyer by raising the price, thus keeping the bottom of NZ society – their hidden homeless from enjoying their human right to adequate housing.

These are long term matters. In the interim, it is requested MBIE review its reading of Section 8 of the Building Act and accept that mobile home manufactured in NZ that are designed to be mobile are not buildings under Section 8, and to advise all Building Control Authorities of this interpretation. Note, this advice does not speak to DIY tiny homes on wheels built by enthusiasts. That question is outside the scope of this brief.

The New Zealand Human Rights Act 1993

The flat-white test

Years ago, then chair of the Auckland Regional Council, Gwen Bull was explaining to a group of senior citizens in a public meeting in the Red Cross meeting hall that the proposed ARC tax increase would cost no more than a flat white a week.

An enraged pensioner stood up and told Bull that she lived on a different planet. If I buy a $4 flat white, that is $4 in food I don’t eat that week.

Civil servants can afford a flat white at Starbucks; they think nothing of it, except perhaps to prefer Mojo’s to the American chain. At the bottom socio-economic sector of society, whom the mobile-home industry serves, will go without food if they spend it on a flat white. The civil servants in Wellington do not comprehend this social divide. They live, as the pensioner said, on a different planet.

That this is happening under Labour’s watch is mystifying. Pundits typically portray National as the party of the comfortable class, but under Labour the statistics for the underclass have grown much worse. But this is because the power lies with the civil service, the team leaders and officers who have career jobs in the ministries and agencies, not the politicians who come and go every three years. The unelected officials read the mood of the politicians, but unless there is a significant interest or core party platform, the biases of the officials tend to drive policy.

The recent Building Amendment exempting 30 m² buildings is a flat-white amendment. You have to own the land to erect a building on it, or afford a lease that is long enough to justify a capital investment in the building. Meanwhile the hidden homeless continue to live in cars, tents, garages. They don’t own land. They own what they can carry. They live day-to-day.

Recently, the New Zealand Human Rights Commission began to investigate the resistance the mobile home industry is encountering with its efforts to provide adequate, affordable housing. In the words of the NZ Human Rights Commission:

The human right to adequate housing is binding legal obligation of the State of New Zealand. This means the State of New Zealand has agreed to ensure that the right to adequate housing is progressively realised in New Zealand. It is an “international obligation” that must be performed in New Zealand. The State has a duty to protect the right of people in New Zealand to enjoy adequate housing and a responsibility to provide remedies…

As a State party to the international human rights treaties that protect the human right to adequate housing, the New Zealand

Government (both local and central) has a duty to respect, protect and fulfil this right. The Government is not required under its human rights obligations to build housing for anyone or to own houses. Its duty is to ensure that all people in New Zealand enjoy their human right to adequate housing. It must do that or it will be in breach of its obligations.

The human right to adequate housing does not simply mean a roof over people’s heads. The United Nations has defined seven standards that must be met in order for housing to be

adequate. [which includes:]

►Affordability: Housing costs should be at such a level so as not to compromise the attainment of other basic needs. For example, people should not have to choose between paying rent and buying food.

The government’s position was recently stated in an email to a MHA member:

The Ministry of Housing and Urban Development is aware that tiny homes, including those on wheels, can provide people with a low-cost alternative home ownership opportunity, and this may be a preferably form of home ownership for some people. That being said, the building of tiny homes, including mobile homes, is not an option that is not currently being pursued by the Government and, as such, the Ministry does not have a formal advisory capacity on tiny homes, including those on wheels.

The reply has some factual errors that need to be addressed first. “including those on wheels” is incorrect because Section 8 of the Building Act 2004 is explicit that a mobile home (aka tiny home) on wheels is not a building, not a structure, and is therefore excluded from the Building Act.

However, the human rights issue has to do with the fact that far more than 8,000 homes are needed. If pre-Covid there were 41,000 hidden homeless, as Housing Minister Salesa says, the government efforts will not be sufficient. NZ Human Rights Commission says:

“The Government is not required under its human rights obligations to build housing for anyone or to own houses. Its duty is to ensure that all people in New Zealand enjoy their human right to adequate housing. It must do that or it will be in breach of its obligations.

Given the severe housing crisis, why is it that “the building of tiny homes, including mobile homes, is not an option that is not currently being pursued by the Government and, as such, the Ministry does not have a formal advisory capacity on tiny homes, including those on wheels”?

Mobile homes are the most affordable, efficient adequate housing available in New Zealand today. More importantly, where the State of New Zealand has agreed to ensure that the right to adequate housing is progressively realised, the mobile home is the best interim solution to enable progressive realisation. It is immediate, but at the same time, does not commit the land in the way buildings do.

A family that seeks to lease a trailer home at say $250/week can afford that rent and still buy food. But if the council says the home is a structure under the RMA requiring a resource consent, and a building under the Building Act, the family must come up with the cash to pay for the consents.

In the free 15-minute consultation, the duty planner will typically ask multiple times who the applicant’s consulting planner will be. Consulting planners are often former council planners who hang out a shingle and charge $300/hour to walk an application through. One professional hour costs more than a week’s rent. Then the duty planner tells the applicant the first thing they must do is to pay a deposit of $3,000 of which the first charge is $500 for a Resource Consent pre-application meeting (using Auckland Council as the example). So the pre-application meeting costs two-weeks rent and the deposit six weeks plus additional thousands for the consulting planner.

By this time, the applicant, who struggled to come up with $500 for first and last weeks rent, breaks down in tears, walks out of the free consultation and moves back into their car, tent or their cousin’s garage. Had they persisted however, next they would be told to pay a $2,645 deposit for the building consent.

In the mid 20th century in the USA some southern states instituted a poll tax that disenfranchised African American voters who could not afford to pay the tax. A similar situation exists with mobile homes

New Zealand is a democracy

- Legislature defines the law

- Executive executes the law

- Judiciary enforces the law

This process is called checks and balances. It is fundamental to the constitutional foundation of NZ but in this proposed Act, it is extinguished.

News Flash July 2020

Building Amendment Bill

- Laws always have a section that informs people and the courts as to its subject. What is it about? This proposed Act is about Building Products and Building Methods.

- But in the section that sets out the meaning does not say what a Building Product or Method is, instead it says it is (or is not) whatever the Governor General by Order in Council says it is. This abdicates the role of the legislative and extinguishes the role of the judiciary.

- This means the targets have no protection in the Act and the courts have no external reference.

- It means MBIE can declare a mobile home is a building product, and the courts are powerless to strike this down because words come to mean whatever the executive says they mean.

- This is a threat to the industry and to democracy.

9A Meaning of building product

(1) In this Act, building product means a product that—

(a) could reasonably be expected to be used as a component of a building; or

(b) is declared by the Governor-General by Order in Council to be a building product.

(2) However, a product that would otherwise be a building product under subsection (1)(a) is not a building product if it is declared by the Governor-General by Order in Council not to be a building product.