Factory-made Mobile Homes – before we get to safe, healthy & durable

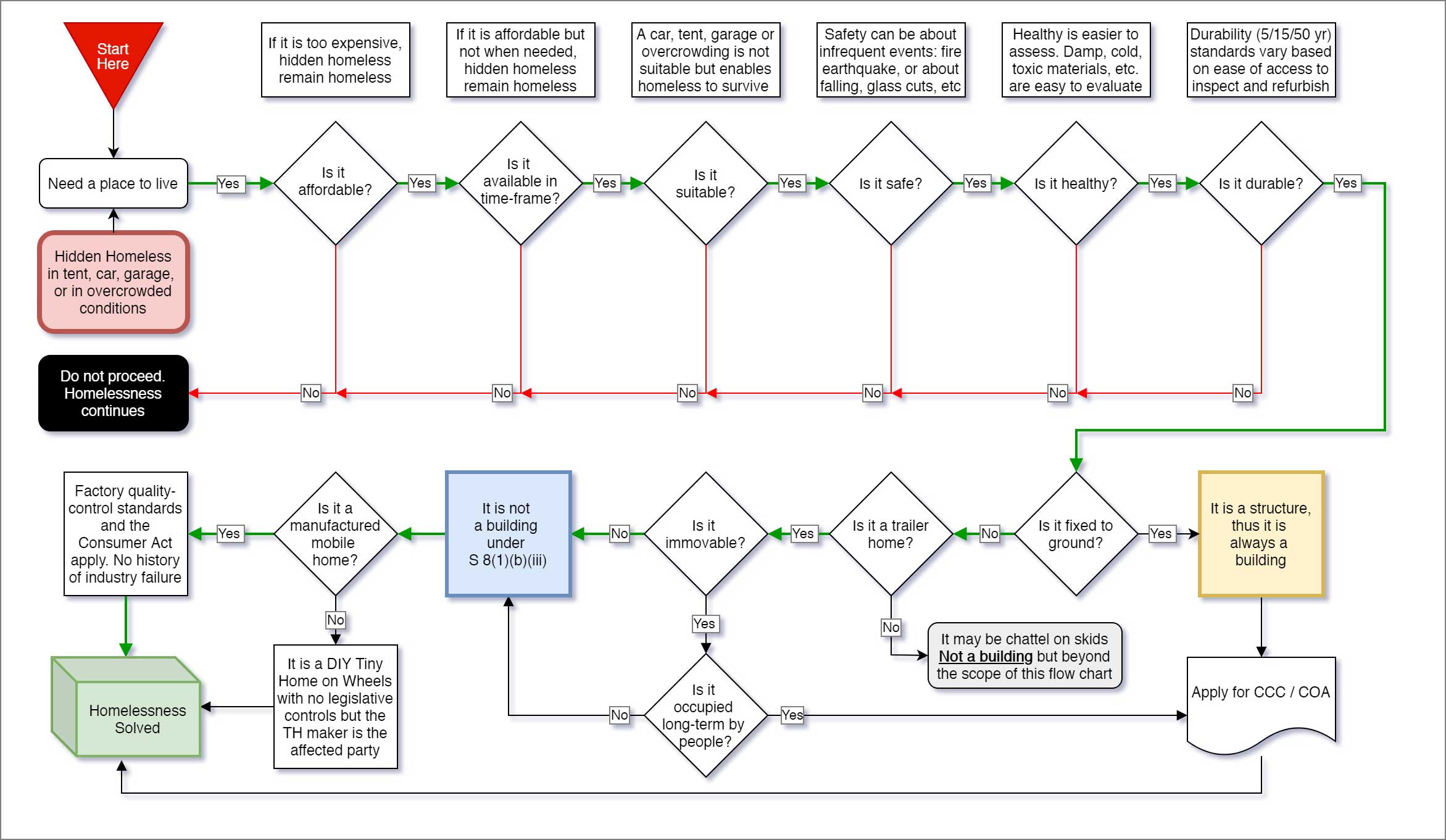

If it is not affordable, government fails. If it is not available, government fails. Health, safety & durability only come into play if it is (first) affordable and (second) available.

Three questions that came out of a conversation with Kainga Ora

Where do mobile trailer homes (not tiny homes*) fit into the mix?

They are immediate, affordable and they do not commit the land.

Is it correct that mobile trailer are not buildings?

Yes. The law is very clear on this, but the cultural bias in Wellington clouds the issues

Is there readily available land for mobile trailer homes that does not involve the same complications as with building projects?

Yes

The short answers for those in a hurry

Where do mobile homes fit into the mix?

Mobile homes are an immediate, affordable and removable solution that can be implemented now, as a 15-year interim solution. They can be moved onto temporary sites (5-15 years) to allow central & local govt. the time it will take for proper, sustainable long-term planning & implementation.

2. Can Kainga Ora proceed without COA’s?

Yes. The law is very clear for anyone who reads it. MBIE’s interpretation that mobile trailer homes are movable structures was rejected on 19 Feb 2020, when the court clarified that mobile trailer homes must be tested under Section 8(1)(b)(iii) not 8(1)(a).

3. Is there available land for mobile homes?

Yes. There are four immediate types of land:

1. Campgrounds in decline for years

2. Whenua-not-real-estate kainga villages

3. Accessory units on existing building sites

4. “Reverse land-banking” of prime farm land

————————————————————————

The Long Read for those who want to understand the issues and the answers

01

Intervention: Where Mobile Homes Fit in the Affordable Housing Scheme.

Buildings are permanent. Mobile Homes are mobile. Mobile homes are an immediate, affordable solution that is made in a factory in a month, install on the site in a day and be removed in a day when needed elsewhere. New real estate development takes months, sometimes years to implement, and when it does it changes the land use forever. Mobile homes do not. Whereas a KiwiBuild home costs $600,000, a 1-2 bedroom mobile trailer home with kitchen and bath costs about $60,000, leases for about $250/week or a low-income applicant can do a rent-to-own for about $320/week. In the affordable housing scheme, mobile homes are the front line, immediate, affordable solution that can be redeployed anywhere in a matter of hours.

The units are not buildings under the Building Act, not structures under the RMA, they they avoid entanglement in consenting processes that can add $30,000 before moving in. Such consents can take months thanks to consenting processes that have reached a level of incoherence and complexity that raises serious issues as to whether they are workable.

The units are chattel (personal property), not real estate, thus they are parked on the land under a right to occupy – sometimes a formal contract, but often just simple permission by the land holder because removing them is so simple: unplug and tow.

In the overall housing scheme for Kainga Ora, MSD, HNZ, WINZ and other housing organisations, mobile homes are like manuka trees, the first colonisers that are later overtaken by longer-lasting plants that establish permanence.

- Single: Mobile homes can be placed one-by-one in residential neighbourhoods, to meet an immediate, crisis-driven need. Daughter with two kids in a relationship breakup, parents say OK, park the mobile home in the back yard. Or the old person needs supervision, but wants autonomy: lease a mobile home for Nanna/Grandpa and park it in the back yard.

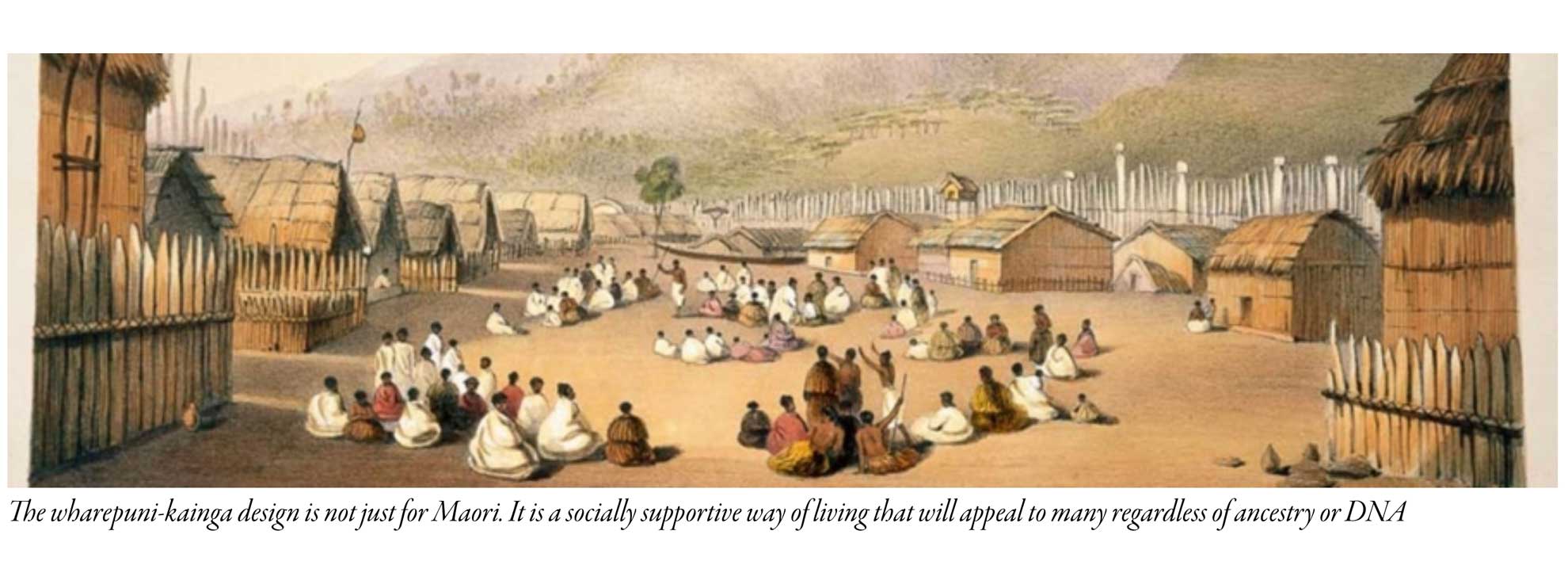

- Multiple: Mobile homes can also be placed in pop-up villages based on the Maori precolonial wharepuni kainga – a village that has small residential homes because it has a socially-enriched public life on the same land. This is discussed below. To be clear, the wharepuni kainga model is not solely for Maori. It is for anyone who wishes to be part of an inclusive community where people know and support each other . This need will be greater as NZ emerges from Covid-19 and the state of the nation’s economy becomes clearer.

On 25 March 2020, everything changed in New Zealand, and the current 41,000 hidden homeless could easily balloon out to 3-5% of NZ population. These people will need housing now. They can’t wait the months and years it will take for buildings. The mobile home housing model has been active in NZ for decades, and long predates villages and towns in human history. It is human-scaled living that provides the basics – warm, dry, safe and comfortable place to sleep, a bathroom and kitchenette at an affordable price even for the person on the benefit or the person earning minimum wage. Its most important quality however, is its immediacy. Unencumbered by the consent costs and delays associated with buildings, it is a here-and-now solution.

Bottom line, NZ needs thousands of mobile homes deployed as fast as the industry can make them. NZ also needs its domestic factories to go to 24/7 manufacturing to provide employment and get cash flowing in the economy (do not spend the cash in China, for example). The need for these mobile units will not go away. Unlike buildings that are fixed in place, mobile homes can move. When people move into permanent affordable housing, the units will not sit empty, they will be redeployed. If the tourism market comes back, some will be on cycle trails. If the Alpine Fault or Hikurangi Subduction Zone breaks, some will be deployed as Civil Defence housing (or for other lesser catastrophes, like the Gore floods in February 2020).

As of 25 March 2020, one NZ mobile home factory has switched to making mobile emergency medical units on 3-month leases (see the photo). When the specialist need passes, they will be returned to the factory and refitted as residential units.

The factories need solid, large contracts to make the investment in hiring and training new workers and upgrading tooling to become more efficient, producing units faster while lowering costs due to economies of scale.

02

Interpretation: Why it is wrong to classify mobile trailer homes as buildings

MBIE Determinations: 1 October 2019, Katie Gordon, MBIE manager determinations wrote:

As noted in a recent determination (2019/036), some earlier determinations focused on the test in section 8(1)(b)(iii) and whether something was immovable and occupied on a permanent or long term basis, but did not consider in any detail how a vehicle may be different from a structure that is movable under the general definition in section 8(1)(a). I remain of the view set out in recent determinations that there is a difference and that this must be considered in each case. I am also of the view that this approach is in line with the Court of Appeal judgement (Thames-Coromandel District Council v Te Puru Holiday Park Ltd [2010] NZCA 663). There are currently two appeals lodged with the District Court that involve this issue of interpretation and it is anticipated that the outcome of those appeals will assist in clarifying this and some related issues for the sector.

Law: In 2019, MBIE sought to “move the dial” by testing mobile trailer homes against §8(1)(a): “is it a movable structure?” rather than §8(1)(b)(iii): “is the permanent dwelling a mobile trailer home?“. On 19 Feb 2020, Judge Callaghan clarified in his ruling on one of the two cases to which Gordon referred:

[29] The reference in s 8(1)(b)(iii) of the Building Act to the LTA definitions is clear. The section states that a building will include a vehicle or motor vehicle (“including” a vehicle or motor vehicle as defined in the LTA), but only to the extent that the vehicle is immovable and is occupied by people on a permanent basis.

The court clarified: a mobile trailer home that is not immovable is not a building. Therefore it does not require a building consent, CCC or COA. This is the law. But it is acknowledged that Parliament can change the law, and Parliament takes its advice from MBIE on these matters. Therefore it is important for MBIE to understand why classifying mobile trailer homes as buildings is wrong – it’s like trying to fit a round peg in a square hole.

The court clarified: a mobile trailer home that is not immovable is not a building. Therefore it does not require a building consent, CCC or COA. This is the law. But it is acknowledged that Parliament can change the law, and Parliament takes its advice from MBIE on these matters. Therefore it is important for MBIE to understand why classifying mobile trailer homes as buildings is wrong – it’s like trying to fit a round peg in a square hole.

Rule Creep: MBIE sought to bring mobile trailer homes (or to be more precise DIY tiny homes on wheels) under the control of council BCA’s because Local Government New Zealand was lobbying for such control. Ostensibly MBIE said it was to ensure the health and safety of its occupants, but as can be seen in these news articles, the real pressure came from grumpy neighbours caused by a culture class between tiny home advocates and neighbours who thought the units were ugly and out of character. This is known as rule creep, good intentions that produce bad outcomes.

Different Than Homes: While the legal question has been settled for the moment, there are very good reasons why mobile homes should never be classified as buildings. Unlike DIY Tiny Homes, Manufactured Mobile Trailer Homes already meet fit-for-purpose standards that are different than buildings. They are designed differently, made differently, use different materials, require different skill sets and endure different conditions. Consider the details:

- Chassis: Instead of a foundation fixed to land, mobile homes use a steel chassis that must endure the equivalent of a 4-hour combined earthquake and cyclone when towed from factory to their first parking site. Buildings would fall apart.

- Reversible: Instead of nails, gib and concrete, they use screws and bolts, designed so that every component is accessible for inspection or refurbishment. The 50-year performance standard for buildings is ill-suited for mobile homes.

- Accessible: Units are designed so each component can be accessed, and if need be repaired or replaced in a day. Instead of a foundation, they have a chassis that can be lifted on a car-hoist for inspection and repair. Not like a building.

- Refurbishable: Units are designed to be refurbished every 15 years or so, more like an aeroplane than a building.

- Mechanical Designer: Mobile units are designed by automotive mechanical engineers, not licensed building architects.

- Coach: Mobile units are assembled by skilled coach-builders. LBP builders lack the necessary qualifications and skills.

- Inspection: A building inspector is not trained to inspect a factory-made mobile product made to endure road transport.

- Mass Produced: Factory-made means same unit is mass produced. BCA’s evaluate each building as unique and bespoke.

- Materials: Building-code-approved materials may be used, but it is not best practice; it’s driven by fear of rule creep.

- Where? BCA’s are regional. Mobile homes are national. Does Tasman BCA fly to a Northland prison factory to inspect?

- Cost of classifying a mobile home as a building adds about $30,000 to the $60,000 price. This kills low-end affordability.

- Delay when a mobile home is classified as a building can take months. This effectively kills placement when in crisis.

What should happen: MBIE should make a distinction between manufactured mobile homes and DIY Tiny Homes on Wheels. Mobile homes are built to a high standard that is repeated multiple times and sold to third parties. The current system and current laws work – the system that makes mobile homes is not broken. There has been no crisis like the leaky building crisis that precipitated demand for new legislation in 2004. However, if government feels there should be regulation, it should be fit-for-purpose. It should not be under the Building Act, because that is sloppy, but if it is forced into it, the law should be clear that:

- Law: Manufactured Mobile Trailer Homes are not buildings under the Land Transfer Act, they are chattel, not real estate

- Cost: Total council/government consent charges added to the initial cost should not exceed $500

- Time: Approval should be limited to vehicle registration/WOF and site check, and should be approved within 5 days.

DIY Tiny Homes are a different matter. They are not a commercial product. The state must decide how much it should protect people from themselves. It should define limits: some have suggested DIY means their own tiny home – not for someone else, a place where they intend to reside there for several years, that they do the work themselves (family or friends can help but must be unpaid), and if they sell it after several years, procure an engineer’s healthy & safety report that informs the buyer. But to be clear, DIY THOWs are outside the scope of this brief. NZTHA speaks for DIY makers. MHA speaks for manufactured units only.

03

Location: Is there land available right now?.

Kainga Ora faces a problem with permanent building projects. There is a lack of available land with the right zoning. Immediate solutions are difficult, and will continue to be difficult until the Urban Development Bill becomes law.

This is not a problem for manufactured mobile trailer homes. There are four immediate land types that are available

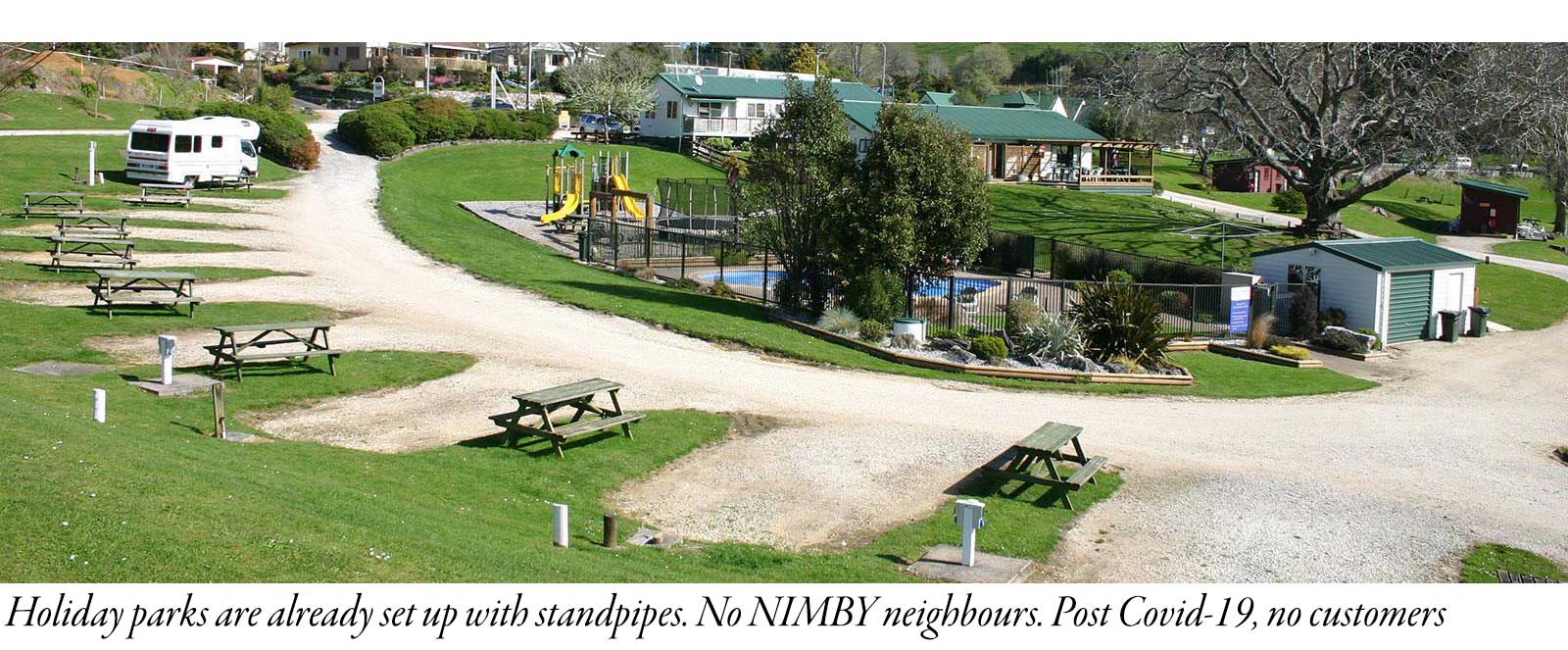

HOLIDAY PARK/CAMPGROUND OPTION: At one time, middle and working class New Zealanders owned a caravan they towed to a holiday park or campground. Few do today, and until Covid-19 most were overseas visitors in campervans or freedom campers in cheap cars when they needed a shower. That market collapsed on 25 March 2020. Even before the collapse there were hundreds of campgrounds throughout NZ available for sale from private owners wishing to retire or on long term lease from councils. While there are limits on paper about how long a caravan can be parked at the campground, in many areas councils have overlooked this, officially or not, so that NZ’s most vulnerable have a place to live. Many of these are hidden slums, with residents living in broken down campervans and caravans.

These campgrounds are the most immediate solution because there will be no grumpy complaining neighbours. In fact the land use will improve with the upgrading the quality of living units, and no in-and-out of short-term occupants. The private sector is prepared to upgrade campgrounds if it can secure financing to acquire and clean up the sites. The advantage for this being done in concert with the factories is to provide a stable production flow. Use of campgrounds avoids almost all entanglement with council red tape. They are ready to go.

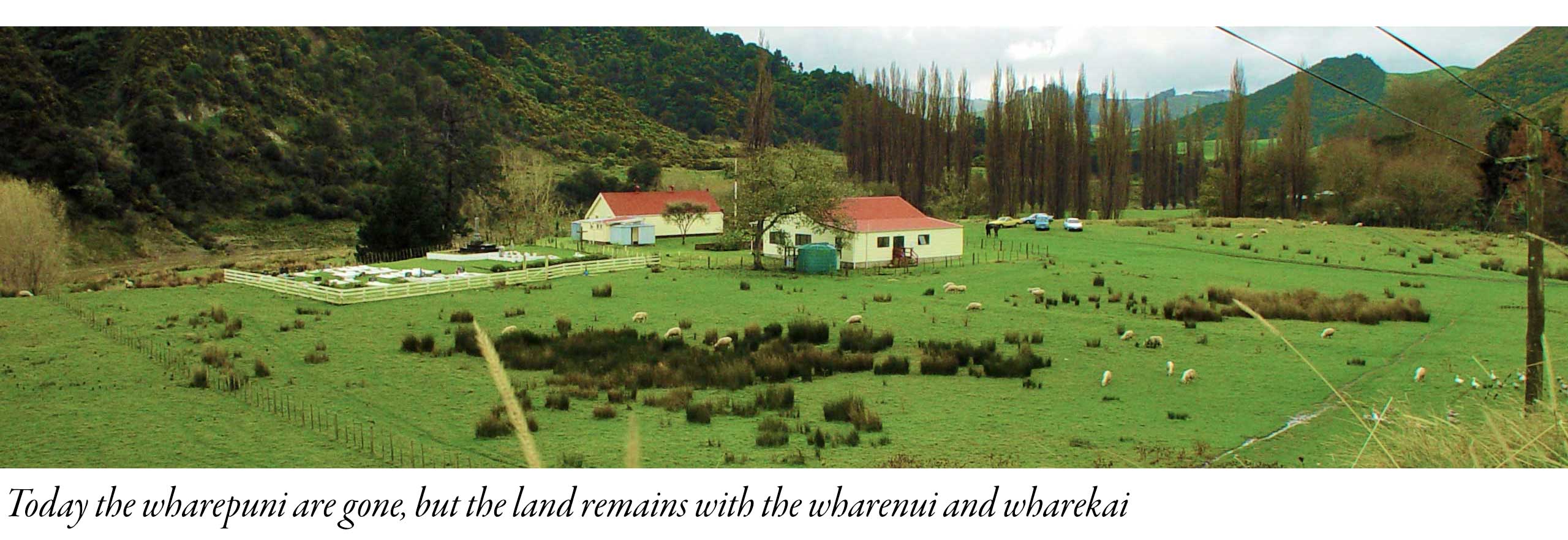

WHAREPUNI KAINGA OPTION: This option is not solely for Maori, but it is based on the timeless, proven development pattern that predated colonisation. It is therefore important to not presume this is solely a proposal for tangata whenua or urban indigenous peoples, but is for anyone who seeks a more socially-enriched and supportive living environment.

In precolonial Aotearoa, Maori lived in Kainga – villages on collectively held land. Unlike the modern marae which consists solely of a wharenui (the large tapu for sacred events, rites of passage, meetings and group sleeping) and the wharekai (the large noa building for food preparation and dining), the pre-colonial marae had numerous wharepuni, the small family homes, as shown in this painting.

In the whenua model, a larger block of land is selected, but not subdivided. The carpark is set near the road, no cars within. The wharepuni (mobile trailer home) sites are set around a large open space (the marae atea) that also has three large marquees:

- The Meeting Marquee for gatherings, childcare and learning

- The Dining Marquee with a BBQ and picnic tables

- The Workshop Marquee with tools where people can make things to use or to sell

INFILL-HOUSING OPTION As discussed above, the manufactured mobile trailer home is a small, mobile unit that can be parked on a residential section to serve as a self-contained accessory dwelling unit (or if no kitchen as a sleepout) for the time it is needed and then towed away when no longer of use. Many district plans have language like this from the Auckland Council Hauraki Gulf Islands Plan “Building means any structure or part of a structure. It also includes any fixed or moveable structure (including caravans) used for residential purposes, assembly or storage.” Note the key word “structure”. In the RMA Structure is defined “structure means any building, equipment, device, or other facility made by people and which is fixed to land”. Thus, a caravan (or in this case a manufactured mobile trailer home) that is not fixed to land is not a controlled or discretionary activity. This is not a loophole. It exists because as soon as any facility is fixed to land it is annexed to title, and it permanently alters the character of the property. In contrast, a mobile home is more like a car. It moves at will and it is personal property, not real estate. Housing NZ owns property throughout NZ. Many of these sites may be appropriate to add infill mobile trailer homes to provide warm, dry, safe and suitable housing for the years it will take central and local government to catch up.

The infill housing option can be used on HNZ land. It also can be used by WINZ where the land is privately owned. The limits to it are normal RMA effects. If a site has an onsite wastewater treatment system that is rated for three bedrooms and there is currently a three bedroom home, consent would be required to upgrade the system before towing on the mobile trailer home and hooking it up. Similar rules apply for site coverage, setbacks and other effects.

It should be noted that manufactured mobile trailer homes are designed to be installed by non-licensed persons. The power uses the higher-standard caravan connection that is plugged into a 16 or 32 amp power point. The water uses a potable water hose, similar to a garden hose. The wastewater uses a caravan-type connector.

REVERSE LAND-BANK OPTION: New Zealand is writing the National Policy Statement for Highly Productive Land which is good in theory, but has a problem. Very few farmers in New Zealand make high-productivity use of highly productive land. Typical land use in NZ looks like this:

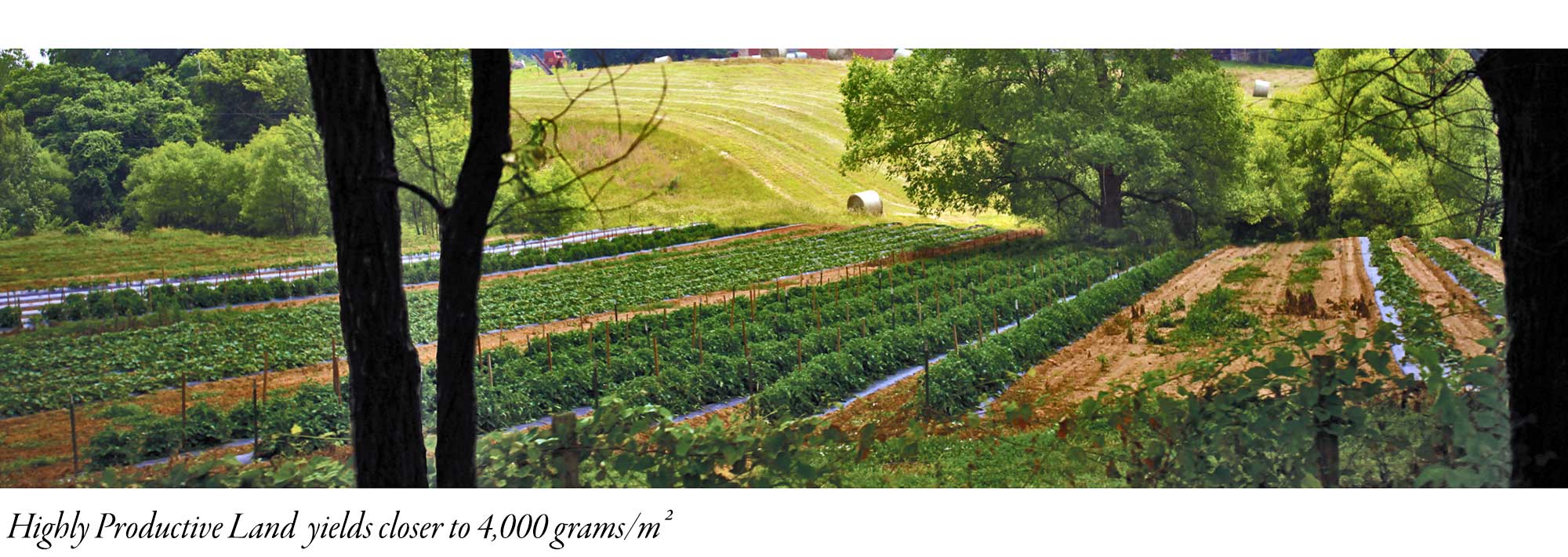

Highly productive land looks more like this market garden, where soil science is used to restore the topsoil to premium quality so it can grow nutritious foods with yields far greater than what passes for normal in New Zealand in 2020. New Zealand has one of the best combinations of mild-climate, year-round water, clean air (no industry in the Southern Hemisphere) and low-population density in relation to arable land. However, the planet does not need it to run highly productive farming. Not now.

The problem: Food, clothing and shelter are the three primary needs of human beings. In 2020, New Zealand does not have a food crisis, but does have an affordable shelter crisis. In recent times, university graduates with planning degrees adopted a green ethos that more resembles a religion than a scientific approach to balancing human needs with those of the planet. They secured jobs in the rule-writing industry, both in local government planning departments and central government ministries where they speak about highly productive farm land without having any idea what they are talking about. Except for the market garden farms that stock NZ supermarkets with domestic food, most NZ land use is exceptionally low in productivity. Dairy produces 80 grams/m² in dairy solids. Beef is 65 g/m². Contrast this with market gardens at 4,000 g/m².

Middle Class Mouths: Barring a pandemic killing billions, scientists project that by 2030, the planet’s middle class will grow by 2 billion. These people will demand a wide range of foods, more than rice and beans, where NZ has some of the finest arable land, mild climate and year-round rainfall to supply those needs. 80 g/m² will be discredited as unproductive land use as NZ will use soil science and technology to feed the world.

Reverse Land-banking: Until then, NZ must preserve its best, but low-production, farm land. Grazing cows, sheep and ponies should not take precedence over affordable housing. NZ needs a type of reverse land banking… finding good use for prime farm land now that can revert to food production when civilisation needs it. Right now, the nation needs land for affordable housing. Not permanent land, but immediate land until councils and central government can catch up – something that given the glacial pace of bureaucracy will take 15 years unless Covid-19 gives politicians the ability to crash the bureaucrats’ party.

How? Mobile homes are placed on not in the land with each having the same right to occupy contract that sets the same expiration date (so all are removed at the same time when land-reversion occurs). Special rules govern topsoil protection, such as no use or storage of chemicals to prevent topsoil contamination that allows the land to be “reverse land banked” to provide for human habitation that is needed now, but revert to prime agriculture land when global demand creates the market.

Pop-up mobile villages are a temporal land use. The units can be capitalised in five years and are typically designed to a 15-year refurbishment schedule. Prime farmland can be prepared with underground pipes and conduit to mobile home standpipes that remain when the pop-up village use passes. The potable water pipes would provide irrigation. The wastewater pipes can provide liquid nutrient supply and the conduit can power robotic farming equipment that may become prevalent in the future.

READ MORE

04

Why in law they are excluded from the Building Act 2004.

Section 8 of the Act sets out the meaning of building. Buildings are structures. A structure is any building, equipment, device, or other facility made by people and which is fixed to land. The Building Act provides a complex definition that begins with the basics (a building is a structure) but then adds further qualifications that specifically addresses the mobile trailer home as an exclusion. The Act says:

building— (a) means a temporary or permanent movable or immovable structure (including a structure intended for occupation by people, animals, machinery, or chattels); and

(b) includes— … (iii) a vehicle or motor vehicle (including a vehicle or motor vehicle as defined in section 2(1) of the Land Transport Act 1998) that is immovable and is occupied by people on a permanent or long-term basis;

On 17 May 2019, MBIE Manager Determinations sought to test if a mobile trailer home (in that case a DIY Tiny Home on Wheels) would fit under the first part of Section 8 as a “movable structure”. On 19 Feb 2020, that determination (2019/017) was the subject of Dall v MBIE, where Judge Callaghan rejected that test. The judge wrote:

[29] The reference ins 8(1 )(b )(iii) of the Building Act to the LTA definitions is clear. The section states that a building will include a vehicle or motor vehicle (“including” a vehicle or motor vehicle as defined in the LTA), but only to the extent that the vehicle is immovable and is occupied by people on a permanent basis.

The Manufactured Mobile Trailer Home industry has always understood this to be the case, and has carefully designed its trailer homes to fit within the exclusion. Note, this is an exclusion, not an exemption like the 10 m² exemption. Therefore while trailer homes are designed to be occupied by people on a permanent basis (as opposed to caravans which are too narrow and not designed for winter living), they are not designed to be rendered immovable. They are not designed to be attached to a foundation, and if someone does attach it to a foundation, the unit becomes a building subject to the Act.

05

Why in fact they are excluded from the Building Act 2004.

The Building Act was written because buildings are large, complex structures constructed in situ by multiple independent contractors, each of whom must get it right, or the building performance can fail. Sometimes these failures can take years to become evident and can cost hundreds of thousands, even millions of dollars to fix. The Building Act designates the Building Control Authority (BCA) as the inspector of the complex designs to ensure health, safety and durability and to ensure the materials used and the performance of the various licensed trades and professions all adhere to the plans.

The Building Act was not written for small, simple manufactured dwellings that are made in factories by a single company that follows standard operating procedures to manufacture the same product many times using a single design. Further, the Act was not written for products that must endure the equivalent of a combination 4-hour earthquake and cyclone before they are set up on the first customer’s location. Licensed Building Practitioners are not trained or qualified to design or make mobile products that must hold together whilst travelling at speeds of 80 kph on the worst of New Zealand roads. Further, such products are designed so that every component is accessible within a day, including the substructure which can be inspected and repaired from underneath by lifting the unit on a standard car hoist at a nearby vehicle repair shop.

When the Act was written, the authors and Parliament were aware of mobile trailer homes. This is why Section 8(1)(b)(iii) is so explicit in excluding them from the Act unless they are rendered immovable. Further, a careful reading of the Section will show that whilst a structure intended for occupation by people, animals, machinery, or chattels is considered a building, an immovable trailer home is not considered a building if it is intended to be occupied by animals, machinery, or chattels. In other words, if a trailer home is used as a chicken coop, or a tool shed or to store personal property, even if made immovable, it still is not a building. Unlike structures, immovable mobile trailer homes are only buildings if they are occupied by people long term.

The authors of the Building Act were well aware of the mobile trailer home industry in 2004. The industry existed in NZ long before the Tiny Home Movement became popular, but for the most part, it was a relatively invisible industry serving the hidden homeless. Because these units are simple and small, they are not deemed to need the additional protection of the Act.

06

How the term “motor vehicle” causes confusion

People associate the term motor vehicle with cars, trucks and buses. The Land Transport Act however, has a broader meaning: a vehicle drawn or propelled by mechanical power; and (b) includes a trailer”. The value of using the LTA meaning is in setting an expectation on physical size without being prescriptive in the Building Act. The reasonable height is 4.25 m because over that it interferes with power lines and may be too high to fit under bridges. The reasonable length tends to be about 12 m. The width varies. A Category One overwidth is 2.56 to 3.1 m and most trailer homes are in this range. A few go to Category Three overwidth which is 4.5 m, but these require pilot vehicles and more limitations because of transport logistics.

The confusion comes when people say things like “”…some tiny house builders and owners appear to be claiming that their homes are vehicles, possibly in an attempt to get around the Building Code.” This is wrong. The Building Code is very clear that mobile trailer homes are outside the authority of the Building Code, and for good reason.

This manufactured mobile trailer home is clearly a trailer which under the LTA is a motor vehicle. It is designed to be safely, albeit infrequently, transported on public roads. Its width, length, height and weight is governed by road rules, not building rules. Building designers do not concern themselves with size, except to fit the land upon which the building will be permanently fixed. Building engineers do not concern themselves with weight because the building will never move once constructed in situ.

This is why the law specifically and clearly excludes such units that are permanently occupied by people unless they are made immovable, whereupon they become a permanent part of the land. Made immovable does not mean held by gravity, it means attached to a foundation, made so it will never go anywhere until it is time to demolish it and remove the scrap.