National Planning Standards (NPS)

A de facto institutional racist, ageist and elitist standard slipped in that hurts NZ’s most vulnerable

The Government is introducing National Planning Standards (NPS), which are lesser instruments of government called for in RMA section 58B. As secondary legislation, they do not require a vote in the House or to be approved by the Governor General by Order of Council (a vote of the Executive Council). According to Legislation Act 2019 s67(d) such secondary legislation does not automatically trigger drafting by the Parliamentary Council Office (PCO), and it appears the contentious language was not vetted by the PCO but written by the Ministry for the Environment (MFE) staff and presented to the ministers in Cabinet, in this case Hon David Parker and Hon Eugenie Sage for signature.

Among the 22,000 words in the NPS standard terms are four words that should never have been handed to the Minister for signature, and on private enquiry, MHA was informed the Minister had no idea they were embedded in what should have been a standard, non-controversial document. To summarise, the following was embedded

building means a temporary or permanent movable or immovable physical construction that is:

(a) partially or fully roofed; and

(b) fixed or located on orin land;

but excludes any motorised vehicle or other mode of transport that could be moved under its own power. [emphasis added]

When what should have been written should have read similar to the definition found in another Act, the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014:

building means a structure that is temporary or permanent, whether movable or not, and which is fixed to land and intended for occupation by any person, animal, machinery, or chattel.

As secondary legislation, there should be no controversy, but unfortunately, the authors of NPS exceeded their authority by changing meanings deeply rooted in Common Law. It appears to have been done not out of malice but elitism: the emergence of a bureaucratic peerage – a social network that includes appointed public officials in central and local government, trade association and consultants who form a self-confirming, internally communicating tribe that isolates itself from the people. This results in central government officials responding to the complaints of their local council peers reacting to NIMBY complaints. It is the product of a closed system in which checks and balances have been walled out; resulting in government officials failing to understand the foundation of NZ constitutional law, and in doing so are making collateral damage out of NZ’s most vulnerable and least powerful.

The NPS consultation documents show MFE intentionally targeted the lowest cost affordable housing – mobile homes – that have become one of the few adequate housing alternatives for the hidden homeless (people living in cars, tents, sheds, garages and overcrowded conditions). MFE distorted the meaning of one of the most established words in Common Law – building – thus enabling councils to extract thousands of dollars in consent fees for a form of shelter that is not a structure, hence not a building. In doing so, the NPS becomes an instrument of de facto racism, ageism and elitism, and may be a breach of the Human Rights Act 1993.

In effect, the council costs are no different than the US Poll Tax that discriminated against Black voters because they did not have the money to pay it. In NZ, four seemingly-innocent words bar Māori, Pasifika, pensioners, disadvantaged school leavers, solo parents and older divorced women from accessing their human right to adequate housing.

Buried in tens of thousands of words, it is a time bomb. Not disclosed to Hon David Parker, the Minister at the time, it was signed, but its devastating impact will not come to light until council officers issue abatement notices, by which time it is too late. Those local enforcement officials executing the notices will say they are just doing their job.

The NPS definition of “building” turns common law and property law upside down, but its effect is institutionally racist, ageist and elitist. The most vulnerable are hurt.

Institutional racism, ageism & elitism in housing

In 2019, the Ministry for the Environment (MFE) drafted its first edition National Planning Standards (NPS). Embedded in 22,000 words are four words “or located on or” as in “building means a physical construction that is… fixed or located on or in land“. These four seemingly benign words turn 956 years of Common Law upside down while institutionally targeting NZ’s poorest and most vulnerable people. It is institutional de facto racism, ageism and elitism in housing.

De Facto discrimination occurs when an institution targets a particular activity that disproportionately injures a particular, vulnerable class. It does not have to be done out of malice, but only have the effect of depriving a class of people of their human rights – in this case Article 25 of the UN International Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the right to adequate housing – by creating an economic barrier.

$25,000+: In Auckland Council the cash deposit required to submit a consent application is $7,000 and if the complicated application is not written by a $5-10,000 private planner, it is likely to be rejected. For a Māori solo mum on the benefit who receives a housing supplement to lease a mobile home that can go on whanau land, this barrier, which can add up to $25,000 or more including other consents and fees, is a drop dead. It is a barrier no different than the racist poll tax that prevented Black people from voting in US southern states. It is de facto racism.

The Human Rights Act 1993 Part 21(1) names specific classes of people who can suffer institutional discrimination because they are poor or vulnerable – because they have no voice when institutions make rules. Among these groups, when it comes to the human right to adequate housing are:

(f) race: rural and urban Māori and urban Pasifika

(h) disability: disabled persons needing limited family supervision

(i) age: older persons needing semi-autonomous family supervision

(i) age: school leavers forced to leave their whanau due to housing cost

(l) family status: solo parents (mostly mothers) as hidden homeless

(b)(v) dissolved relationship: older divorced women lacking resources

Polarisation: In the past two decades, New Zealand has polarised into two classes of people. Not the 19th & 20th century division between workers and capitalists that gave NZ the red and blue Labour and National Parties, but a new division between the Comfortable Class and the Struggling Class – the Haves and the Have Nots.

Haves and Have Nots: Haves identify with both Labour and National, as well as minor parties. Have-Nots do not have time or energy for political or ideological affiliation, they are focused on surviving. They don’t make submissions to government on proposed new rules. They have no voice.

No Have-Nots in Government: All parties involved with NPS, from MFE employees to their council peers, the Minister and his advisors, and the consultation submitters are of the Comfortable Class. They all have adequate housing. No one involved in this process is a member of the Struggling Class. The whole process is one of a comfortable elite creating collateral damage; completely unaware of the adverse impact of their acts.

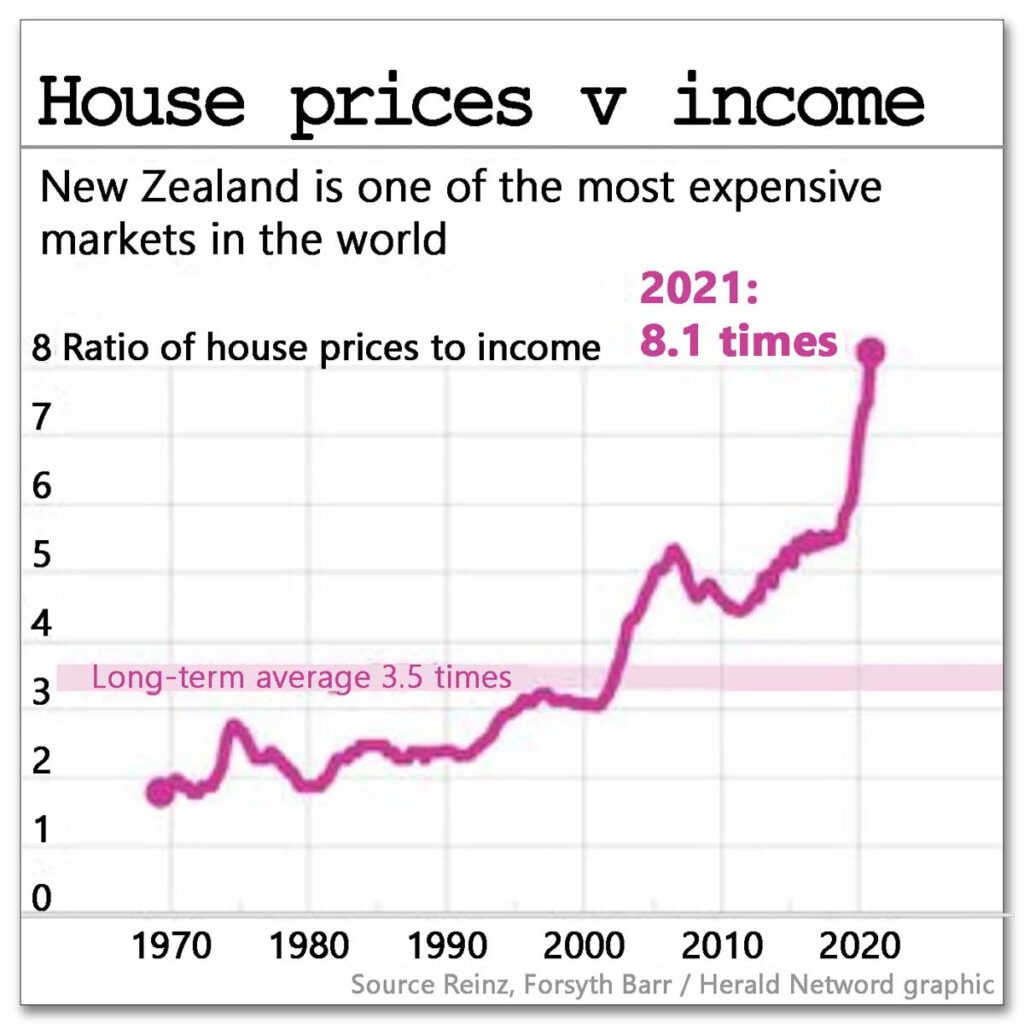

300% increase in cost of housing: The primary cause of this polarisation is the increased cost of one of people’s most basic needs: shelter; a housing market completely out of control. While the median household income rose by 30%, mostly due to inflation, the median cost of a home rose by 300%. The comfortable class complains, but can afford to pay the mortgage or the rent. The struggling class transitions into hidden homelessness – living in cars, tents, garden sheds, garages or overcrowded conditions.

Uncounted / Unseen: These are not the street homeless visibly living rough due to alcohol, drugs or mental disability, but those who lack the power and privilege to negotiate the resources necessary to secure the human right to adequate housing. They are uncounted. They are unseen. They are a recently-created class of Kiwis. When homes were affordable, the Struggling Class did not exist.

RMA: The rise in housing costs, ironically begins with the RMA. When the RMA took over from the Town and Country Act, most district council planners were civil engineers, often having transitioned from a private sector career into the less stressful employment with the council. As population grew, primarily due to immigration, they rezoned rural, undeveloped land into residential to ensure land costs were affordable.

Change in Personnel: But then, a new ethos, a new set of values, changed the role of government: environmentalism. Inspired by a growing awareness that human exploitation of the planet and her resources was unsustainable, a new generation of students began to take degrees in environment planning not civil engineering.

Institutional Insiders: Those students graduated, taking first jobs in central and local government. With no real-world experience, they rose in the ranks. They redefined their roles. No longer comfortable calling themselves civil servants, they rebranded their jobs with the neo-liberal job titles of officers, team leaders and specialists. Mono-focused on protecting the environment from development, the RMA purposes to enable people and communities to provide for their social, economic and cultural wellbeing were given no more than lip-service. Those in charge were trained in environmental protection not economics or civics, hence their fixation on the environment over everything else.

Comment: This is not to discount the importance of environmental protection. Humans are making a thorough mess of the planet – although ironically, the RMA not helping. The RMA is the largest cause of NZ’s CO₂ emissions because its district plans adopted the US zoning model separating home from daily destinations thus requiring the transport that generates 47% of NZ’s CO₂ emissions. Human activities must be changed to protect the environment, but unfortunately, government institutions are doing the opposite. Its actions deplete people’s savings, demean the human spirit and demolish the environment while it greenwashes – spawning reams of useless but expensive and time-consuming official paper.

“The transport sector currently produces 47 per cent of New Zealand’s CO2 emissions and between 1990 and 2018, domestic transport emissions increased by 90 per cent.”

Transport Minister Michael Wood 14 May 2021

Obstacle makers: This new professional class within central and local government did not prevent development, but they turned the permission process into an arduous, expensive process that could take three years and cost millions of dollars in very expensive assessments written by private consultants (their peers and often their former colleagues). More than half the cost of development is permission.

Land Blowout: These costs, that also now include questionable development contributions that appear to fund council overhead, were not borne by the developers; they were passed on to the end buyers. A rural paddock that previously had pony-club horses on it that cost $10,000 per hectare to buy as a rural property would sell for $500,000 per developed 600 m² section ($8 million per hectare). Two decades ago, the price would have been $50,000 for the subdivided section.

That was the first element in the perfect storm that created the struggling class.

Paper Blowout: The cost of architectural designs skyrocketed as councils demanded exacting plans that quadrupled costs. This was done to mitigate council liability. By finding councils were joint and severally liable for construction failures (mostly caused by the prior Building Act that caused NZ to deviate from time-proven building methods), the failings of a few are now paid for by everyone in the cost of paper.

Construction Blowout: Next came the cost of construction. Thanks to a failure of the industry, the rotting house crisis resulted in a new Building Act 2004, which like the RMA, added substantial document and permission costs. Competent builders who earned $25 /hour became Licensed Building Practitioners charging $75+ /hour, flushing out the qualified builders who had been attracted to the industry because disproportionately they suffered literacy disabilities such as dyslexia – they could not read, thus worked with their hands. They quit the industry because they could not read or write the tests.

Materials Blowout: This was followed by the building materials industry pressing for NZ-approval meaning perfectly good, and often superior building products manufactured overseas at far lower cost were barred by Fortress NZ. A nation of 5 million, the population and size of the US state of Colorado, declared it has unique conditions requiring expensive and time consuming certification to be used in NZ. This too was driven by pecuniary interest, not the claimed health, safety and durability.

Paper Chase: In every aspect of the industry, the paper chase overtook the hands-on tradesperson making something, while the industry continued its bespoke approach with each house being a one-off.

Grass-roots Response: This perfect storm created the market demand for the smallest scale of affordable, adequate housing: mobile homes. The word adequate – borrowed from Article 25 of the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights to which NZ is a signatory – is a baseline. It means warm, dry, safe, durable and suitable as an abode but at minimum size and cost. Mobile homes are small, typically 8m x 3m or as small as 6m x 2.5, where size is determined by the design of NZ roads. 3.1 m is the maximum width of a category 1 oversize vehicle.

Excluded from regulations over buildings: While size reduces cost by using fewer materials, and factory manufacture rather than bespoke construction results in lower assembly costs and economies of scale, a major factor in affordability and immediacy was their exclusion from both the RMA as chattel shelter not fixed to land and the Building Act as vehicles that are not structure. In Auckland Council, for example, the simplest RMA consent for a building demands a $7,000 deposit before the automated system will accept the consent application. And if the application is not written by a $5-10,000 consultant, it is likely to be rejected. Similar costs applies to building consent.

Drop-dead Costs: The de facto effects of such costs is to erect an insurmountable barrier for the struggling class – especially in cases where they will lease the mobile home using a $350/week beneficiary housing supplement and have arranged with whanau, family or friend to park it on land rent-free. Where can they come up with $15-25,000?

Hidden Homes: However, until this new NPS interference, only rarely did district councils interfere. The law was unclear in their view (MHA disagrees, it is clear, but does not treat mobile homes as buildings), but most mobile homes going to the struggling class were in back blocks and behind trees, not in Comfortable Class neighbourhoods. They were hidden homes to house the hidden homeless.

What Changed? Tiny Home Movement: As housing costs began to prevent tech-savvy Millennials from joining the property ladder, the tiny home movement was born. These young people came from the Comfortable Class, and soon discovered a home on wheels was excluded from rules governing buildings. Unfortunately for the poor, these new Tiny Home advocates parked their units in nice neighbourhoods inhabited by comfortable neighbours who showed no empathy for the resourceful kids next door, and certainly no concern for their health and safety when the neighbour complained to the council.

The “Do-something” Council Response: The councils felt the heat, so they began issuing abatement notices and notices to fix, asserting the mobile homes were buildings. When they began to experience push-back (see Dall v MBIE in a Building Act case), because the law did not support such interpretations, the local government officials began to complain to their peers in MFE and MBIE.

Consulting on the NPS:

Decoupling: As the record written by MFE shows, the law did not support the assertion that mobile homes were buildings, thus, MFE decided to decouple structure, a term defined in the RMA, from building by making up new words.

MFE wrote:

“Shipping containers have been difficult to manage under the RMA as it is their own weight that holds them down (they are not fixed to land) and small mobile/relocatable buildings have become more common over recent times.”

Missing Questions: What both council officers and NPS authors fail to ask is Why ? and Who?

- Why are small mobile homes becoming more common over recent times?

- Who is buying or leasing these mobile homes?

Why: At the same time median household income rose by 30% (mostly inflation), the median cost of a home rose by 300%. Bottom line, the have-nots drop into the struggling class and many become hidden homeless – people living in cars, tents, sheds, garages and in overcrowded conditions. When offered the affordable lifeline of a mobile home – that costs a tenth the price of a KiwiBuild – they have an adequate housing alternative.

Who: The struggling class is disproportionately represented by Māori, Pacifika, lower-decile school leavers, solo mums, no-asset older single women and pensioners who rented their whole lives, not building equity in home ownership.

Institutional Racism: In targeting their only adequate housing solution, NPS is de facto racist, elitist and ageist. It is institutional racism.

Blind Racism: No doubt, the authors of the NPS would be appalled at such a charge, and respond that they do not have a racist bone in their body. But that is because they have not thought about the Why? and the Who? They don’t see what they are doing. They are blind to the effects as they do their job, trying to word-smith away a pesky problem they hear from their local government peers.

Why this matters: Mobile homes are one of the few affordable adequate housing solutions available to have-not Māori and others in the struggling class, but as soon as they are swept up in the Operative District Plan as a building, their affordability is gone.

IT’S ABOUT MONEY

25 years ago in Auckland the deposit for a resource consent was $150, took as little as 3 days to approve and could be written by a reasonably literate applicant.

Today, an identical application requires a $7,000 deposit, can take months, and is likely to be rejected as incomplete if it is not written by a private planning consultant who adds at least $5,000 to the cost.

Why? Because council departments now have a pecuniary interest to fund their department with fees, fines and contributions. Their official values statements are not aligned with senior management’s expectation the officers meet revenue expectations.

It’s the natural outcome of the Neo-Liberal idea of User Pays. In this philosophy, Governments are supposed to act more like businesses, except as monopolies, they are not subject to competition that spurs better service at a lower cost. There are no checks and balances.

As environmentalist Al Gore said: “You know, more than 100 years ago, Upton Sinclair wrote this, that “It’s difficult to get a man to understand something if his salary depends upon his not understanding it.“

Here is the dilemma. MFE wants to protect the environment. But, the public complains there is no consistency from one district plan to another, and there is a need for key words to mean the same thing everywhere. No argument.

But then, the district planners complain they don’t know what to do with mobile homes and other forms of low-cost shelter that do not meet the definition of structure. It’s not that mobile homes are bad for the environment – indeed to the contrary, they have a much lighter footprint – but the council feel they must regulate them the same as buildings.

But while the RMA says its purpose includes enabling people and communities to provide for their social, economic and cultural wellbeing, it never anticipated the 3:1 home to income multiplier would jump to 10:1 and create a struggling class who clearly are not being enabled.

There is an answer, but MFE missed it, and instead turns property law inside out, in a way that is de facto racist, elitist and ageist.

NPS Meaning of Building

To read MFE’s page 47-55 text, click here.

To read the 234 page document click here

To read the NPS (see p55) 2002 update click here

The issue is a few words… replacing structure with physical construction and inserting or located on or. The former is an ineffective subterfuge, the latter changes Common Law.

building means a temporary or permanent movable or immovable physical construction that is:

(a) partially or fully roofed; and

(b) fixed or located on or in land;

but excludes any motorised vehicle or other mode of transport that could be moved under its own power. [emphasis added]

These simple words (in red) were slipped into the NPS. They were not signalled to the minister that MFE was overturning almost a thousand years of property law. Thus the minister signed off a racist, ageist, elitist and ultra vires national planning standard having no idea what he did.

Why did MFE do this?:

The earlier 234 page background report explains:

…structures that are located on land but not fixed to land on the basis that it is becoming more common for relocatable structures to be used that are not fixed to land. Shipping containers have been difficult to manage under the RMA as it is their own weight that holds them down (they are not fixed to land) and small mobile/relocatable buildings have become more common over recent times.

Based on this concern MFE in its first draft proposed to redefine the words building and structure:

3.14.1 Proposed definition

Building means any structure, whether temporary or permanent, moveable or fixed, that is enclosed, with 2 or more walls and a roof, or any structure that is similarly enclosed

Structure means any building, equipment, device or other facility made by people and which is fixed to or located on land; and includes any raft, but excludes motorised vehicles that can be moved under their own power [underline added]

The problem with this is it is a breach of Legislation Act 2019, which says:

20. Words used in secondary legislation or other instruments have same meaning as in empowering legislation.

Structure is already a part of the RMA:

“Structure means any building, equipment, device, or other facility made by people and which is fixed to land; and includes any raft”.

Given this reminder they were proposing to breach the Legislation Act, in their second try, the NPS authors moved the “or located on” language from structure to their new meaning for the word building, which is not defined in the RMA.

Building is not defined in the RMA, because 956 years of Common Law states that all buildings are structures. Buildings are a type of structure, but all buildings and all structures are always “fixed to land”.

The background story seems to suggest that the MFE lawyers focused on Environment Law and skipped or failed Property Law 101.

Because they could not use their original definition (Building means any structure…), MFE explains that they invented a new legal term, physical construction, explaining that it would embrace not only structures but what property law calls chattel – things made by people that is not fixed to land.

Two problems

- The word construction refers to realty (real property) not chattel, so MFE failed to hit the target.

- To redefine such a fundamental word at law as building is not something done by inserting a few prepositions into a massive document and failing to inform the Minister that MFE just upended a thousand years of common law and property law.

In support of the first point, the clearest statement of meaning is found in US law, where US Federal Government Statutes says:

Construction means construction, alteration, or repair (including dredging, excavating, and painting) of buildings, structures, or other real property. For purposes of this definition, the terms “buildings, structures, or other real property” include, but are not limited to, improvements of all types, such as bridges, dams, plants, highways, parkways, streets, subways, tunnels, sewers, mains, power lines, cemeteries, pumping stations, railways, airport facilities, terminals, docks, piers, wharves, ways, lighthouses, buoys, jetties, breakwaters, levees, canals, and channels. Construction does not include the manufacture, production, furnishing, construction, alteration, repair, processing, or assembling of vessels, aircraft, or other kinds of personal property

It is likely that if the NPS meaning of physical construction was tested in High Court, it would be limited to real property and not include personal property (chattel) that is not fixed to land. Although it is more likely the court would toss the definition out entirely and instruct MFE to try again or to use the standard meaning, as best found in Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014:

building means a structure that is temporary or permanent, whether movable or not, and which is fixed to land and intended for occupation by any person, animal, machinery, or chattel.

structure— (a) means a thing made by people, whether movable or not, and fixed to the land; and (b) includes equipment or machinery

What was MFE thinking?

MFE clearly set out its thinking in the consultation documents prepared by MFE.

In this publication:April 2019 Ministry for the Environment publication (ME 1404) 2I Definitions Standard – Recommendations on Submissions Report for the first set of National Planning Standards, MFE wrote:

RMA plans seek to manage effects from buildings in the main where those effects are more long term than from, for example, a car parked on a section and used every day. However, where those vehicles no longer move (likely no longer used for transportation but for activities such as business, storage or accommodation) we consider they would have similar effects as buildings and should be captured by the definition. We therefore recommend excluding motorised vehicles or any other mode of transport that could be moved under its own power.

We considered the alternative to exclude vehicles where they are used for business, storage or residential activity – but given the fact that the definition applies to facilities that are located on land – the definition would then have encompassed any business vehicles or even trucks when located or parked on land. We consider it is more certain to only exclude those vehicles that can be moved under their own power.

It also wrote

We considered other terms which could be applied instead of ‘physical construction’. We tested the word ‘facility’ with our pilot councils and they queried the meaning and certainty of that word. They sought clarity about whether some items such as shipping containers, caravans, motorhomes or house trucks would come within the meaning of the term. We consider that part of the uncertainty about that word relates to the fact that ‘facility’ may bear the meaning of a larger building or complex often used for a public or community purpose (eg, educational facility or community

facility). We consider that the term ‘physical construction’ carries the meaning of a structure that is manmade and tangible, but it does not need to be fixed to land. While this is a new term, we consider that it is broad enough to cover all types of buildings without setting any parameters other than that there must have been some form of manmade construction. It will not be taken to exclude some items because they don’t qualify; as the word ‘facility’ may have been.

Then comes the part that suggests the MFE lawyers either did not read this commentary or have insufficient training in property law:

As referred to above, the removal of the word “structure” from the definition of building, decouples a building from the requirement to be fixed to land which is specified in the RMA definition of “structure”.

Middle Level public servants working in a government ministry do not have the authority to decouple such fundamental words in law as building and structure.

The Problem with Writing Standards

New legislation has the benefit of vetting by the Legislative Design and Advisory Committee (LDAC) or the Parliamentary Council Office (PCO) that examines drafts to ensure they are consistent and understood by ordinary people. Referencing Legislation Guidelines the 2021 edition, CHAPTER 14 Delegating law-making powers, Part 1: Is the matter appropriate for secondary legislation?, makes it clear when regulations become ultra vires. In particular:

The following matters should generally (or in some cases always) be addressed in primary legislation:…

variations to the common law.

Redefining the meaning of building to include chattel (personal property) is a fundamental variation to the common law and one most unlikely to pass vetting by LDAC or PCO.

Conclusion

The NPS meaning of building is de facto racist, ageist and elitist, and an argument can be made that it is in breach of the Human Rights Act 1993 Part 21(1).

The meaning fails to achieve its purpose, because physical construction generally refers to realty (real property) not chattel (personal property).

The conflating of chattel and realty fundamentally alters the common law, and is likely to be found to be ultra vires – that a Minister signing off a standard that changes the common law to an opposite meaning exceeds his powers as delegated in Section 58B of the RMA.

A standard definition of building should be used – as best found in Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014.

If there needs to be new definitions for chattel used as shelter, as abodes and other purposes, they should have new, but familiar terms. And for clarity, fixed to land should include clear tests that respect case law and common law as discussed elsewhere in this site.

Recommendation

Remove the NPS meaning of building as found in the first edition.

Replace it with the same language as found in Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014:

building means a structure that is temporary or permanent, whether movable or not, and which is fixed to land and intended for occupation by any person, animal, machinery, or chattel.

Additional Recommended Language

MFE is correct, the existing legislation did not anticipate what MHA calls chattel shelter because conventional buildings were affordable by all. Given the fundamental change in one of human beings most basic needs, shelter, new terms should be introduced.

However, given their role as providing adequate housing for NZ’s most vulnerable, the definitions should include a reference to poverty solutions so the council charges do not undermine its mandate to provide for the social, economic and cultural wellbeing of people and communities, as set out in RMA Section 5 – Purposes.

Basic Terms

Fixture: Means the same as in Common Law. Any physical property that is attached to the land in such a manner that it becomes part of the land, and loses any independent identity. For clarity, structures are a subset of fixtures and buildings are a subset of structures; all buildings are structures, all structures are fixtures, all fixtures are realty and all realty is either land or property fixed to land.

Fixed to land has the same meaning as in Common Law, meaning physical property that is annexed to the land in such a matter that it becomes part of the land. For clarity, fixing to land may be formalised by recording the act on the Land Information Memorandum (LIM), or if examined by the courts, is a matter of degree determined by the facts.

Chattel has the same meaning as in common law, meaning physical personal property that has its own independent identity.

Movable means a building, structure or fixture that moves, such as a pontoon fixed to a pier that moves up and down with the tide and may occasionally be removed for repair or maintenance, or part of a building that moves, such as a windmill that pivots in the wind. For clarity, moveable is not the same as mobile where the object maintains the independent identity of chattel, such as a vehicle manufactured as a mobile home.

Mobile: means chattel capable of easily being moved on and off land without taking the chattel apart or significantly damaging it in the process of removal. For clarity, chattel remains mobile even if it is strapped to land to prevent movement in high wind, blocked on corners to prevent motion when stationary and in use, or if two such units are physically bolted together, provided the bolts are easily accessible and can be removed by a non-licensed person without significant damage to the property. Also, for clarity, mobility is lost if the property is fixed to a foundation, piles or other permanent footing, and/or if connection to services, including electricity, water, waste water or other utilities requires the services of a licensed professional (such as plumber or electrician), but mobility is not lost if an ordinary person can connect and disconnect services. Further, mobility can be lost if the chattel becomes landlocked where it cannot be removed from the land except by taking it apart. Mobility is not tied to NZTA current registration or warrant of fitness.

Pods, Mobile Homes and Box Trailers

Pod: From the words portable on demand, pod, is also known as a box trailer, means physical chattel property that

(a) is designed to be towed intact on wheels by a powered motor vehicle on New Zealand roads and

(b) is no larger than NZTA Category Two Over-dimension vehicle, and

(c) is intended to provide temporary or permanent, mobile shelter for people, animals, machinery or chattel, or storage that provides physical security and protection from the elements by weatherproof floor, walls, roof and joinery and

(d) is not fixed to land, not annexed to title and if it has utilities, such as water, waste-water or electricity, that such services can be connected and disconnected by any person.

For the purposes of planning and planning consent the footprint of a pod shall be evaluated the same as a building for the purposes of enforcing site coverage, boundary setback, height and height in relation to boundary and other relevant conditions, with consideration given to the fact that pods do not commit the land in the same way as buildings. When placed on land, the wheels, draw bar, lights and registration plates may be removed and stored for protection and to enhance visual amenity.

In the determination of recoverable charges, pods shall be licensed, not consented, with a nominal fee, to ensure the human right to adequate housing is not deprived by cost associated with consenting.

Mobile Home: a pod that remains mobile, remains not fixed to land and intended for temporary, long-term or permanent abode by any person. For the purposes of wastewater planning, every bedroom in a mobile home that is placed on a lot shall be counted the same as a bedroom in a building.

Manufactured Mobile Home: A mobile home manufactured in a domestic or overseas factory by a New Zealand, intended to be sold to anyone and can include a kitset where the components are towed on site on a chassis and the buyer assembles the pre-manufactured components according to the manufacturer’s instructions and performance liability.

Tiny Home on Wheels: A mobile home made without compensation – other than subcontractors hired by the owner – that is made as a one-off by the maker, for the maker or for its friends or family and which is intended not to be sold to an unknown third party for no less than two years from the date of completion.

Wharepuni: Small family homes typical of pre-colonial Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu where whanau slept and sometimes maintained a home fire, updated in the 21st century to include pods of a similar size and function.

Kāinga (mo te tangata katoa o Nu Tirani): Based on precolonial development model, a community design intended for any persons (nga tangata katoa o Nu Tirani), set out around a marae ātea that includes a wharenui (large community meeting hall), wharekai (large community dining hall), multiple wharepuni where families live and in some cases multiple whare-whaihanga (workshops to earn a living) and wharepaku (toilet blocks)

Workplace Pod: a pod intended for use by people when working and/or for storage of chattel or machinery.

Visitor Accommodation Pod: a pod intended for overnight accommodations with stays limited to 30 consecutive days by the same persons that may include a self-contained bathroom and kitchenette.

Wet Pod: a pod that includes water and/or wastewater connections

Dry Pod: a pod that does not include water and/or wastewater connections

Waterless Separator Toilet: A toilet where urine and faeces are captured separately, collected and transported off site for disposal, including off-site composting.

Recirculating Shower, Sink and Basis: Sanitaryware that is charged with a small amount of potable water that is captured in the drain, filtered, purified, reheated and recirculated as sanitary potable water for the duration of the use cycle.

Portable Modules

Transportable Module: The same as a pod, except not having an integrated trailer chassis, but instead is manufactured with skids where the module is designed to be transported on truck or on a separate trailer on New Zealand public roads with a size not to exceed Category 2 Oversize. The rules for pods apply to modules, except in relation to rules related to the under-chassis trailer.

Converted Shipping Containers

Converted Shipping Container: An intermodal shipping container manufactured to ISO standard 668.2020 that has been converted to use on land, including use as storage, commercial activity, occupation by people, animals, machinery or chattel that is not fixed to land. For the purposes of planning and planning consent the footprint of a converted shipping containers shall be evaluated the same as a building for the purposes of enforcing site coverage, boundary setback, height and height in relation to boundary and for waste water capacity if relevant, and other relevant conditions, with consideration given to the fact that such modules do not commit the land in the same way as buildings provided they remain as chattel, not fixed to land.

Converted Storage Container: A container converted for storage of goods, material and chattel that is infrequently accessed by people.

Converted Abode Container: A container converted for occupation by people on a long term basis

Converted Visitor Accommodation Container: A container converted for occupation by visitors for no more than 30 days per stay.

Converted Container Shops: A container converted for retail sales to the general public.

Converted Food Service Container: A container converted to sell food and drink to the general public.

Converted Wet Container: A container with Sanitaryware including but not limited to showers, basins, sinks, dishwashers and clothes washers.

Converted Home Office Container: A container used as a home workplace.

Other Converted Containers: A container converted for an activity other than those described herein.